Filichia Features: The Gospel Truth on Godspell

Filichia Features: The Gospel Truth on Godspell

On March 8, 1971, Stephen Schwartz – making all of $22.50 a week thanks to one of his songs -- agreed to provide music and some additional lyrics for an upcoming off-Broadway show.

Never mind that he had to have everything ready in thirty-four days. The composer-lyricist who’d just passed his twenty-third birthday was hungry and crazy enough to say yes.

Original Album Cover

Original Album CoverA mere fifty-three weeks after he’d accepted the assignment, Schwartz and Godspell were getting a Grammy Award for Best Score from an Original Cast Show Album – besting shows by Bock and Harnick, Rodgers and Charnin and – oh, yeah – Stephen Sondheim, who “only” wrote Follies. No one knew it at the time, but of all the original cast albums issued in the ‘70s, Godspell would stay on the charts longer than any other – a full sixty-one weeks.

Seven months before those Grammys, Godspell was such a hit that it had moved to a theater with almost three times as many seats. And the Grammy was not Schwartz’ first award for the show; he’d received a Drama Desk Award the previous June.

With success such as this, producers came courting. Now Stuart (1776) Ostrow would present Schwartz’ Pippin with Bob Fosse at the helm come autumn.

And so began one of the great careers in musical theater history, as is evidenced by Schwartz’ getting an Honorary Tony this June 7.

Want more of the story? Then get Carol de Giere’s comprehensive and always entertaining new book, The Godspell Experience, which we’ll celebrate along with Godspell's forty-fourth anniversary on May 17.

But Schwartz isn’t a presence for the first part of the book. John-Michael Tebelak was the Carnegie Mellon University student who thought existing church services were on the stodgy side. “Instead of resurrecting Christ,” he said, “they pushed Him back in the tomb.”

So while Tebelak was at school, he wrote and directed The Godspell. (Yes, just as Facebook was once Thefacebook, Godspell was once called The Godspell.)

Tebelak took famous Gospel stories (mostly but not exclusively from Matthew) and filtered them through clowns. This concept had eight of the ten actors cast wanting to quit. Actress Gilmer McCormick was especially wary, for she was a minister’s daughter.

Not until the cast members started painting each other’s faces in clown make-up did they start to come around. Actor Bob Ari saw it as “Challenging authority in a clownish way.”

Tebelak was a true theater puppy, often living behind the stages for which he wrote and directed. As a fan of Peter Brook and MARAT/SADE, he had some wild ideas for The Godspell, including having the actor playing Jesus sing “Oh, God, I‘m busted” and appear in the nude.

The former happened; the latter didn’t.

Songwriter Duane Bolick did the score, although Tebelak found room for a melody he’d liked from classmates Jay Hamburger and Peggy Gordon. Their tune, “Marigold Song,” morphed into “By My Side.”

After the show had had a successful run at school, an unexpected opening at LaMama allowed Godspell to come to New York. Stephen Nathan, who’d been Jesus at CMU, was all set to open a food store in Pittsburgh when he got and answered the call. Nathan saw Jesus akin to “the Shakespearean fool – the only one to tell the truth.” Jesus, then, was the hub of the wheel while all others were the spokes, each of whom became His spokesperson.

Edgar Lansbury – producer of the Pulitzer Prize and Tony-winning The Subject Was Roses – saw the show and said “The story-telling was wonderful, but a lot of the music wasn’t.” He suggested that Tebelak recruit that other CMU student who had written a campus musical called Pippin Pippin. (Apparently, Schwartz thought his musical about Charlemagne’s son was so nice that he’d named it twice.)

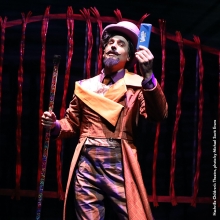

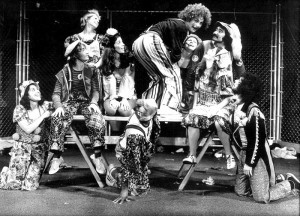

Stephen Schwartz and the Godspell Company, 1971

Stephen Schwartz and the Godspell Company, 1971

Tebelak remembered Schwartz as flamboyant. “My whole freshman year I used to walk around in a cape,” the songwriter now admits. (Ev’rybody has to go through stages like that.) Still, Tebelak okayed a meeting and Schwartz responded because he saw the show as one where “eight strangers start out increasingly hostile to each other’s ideas and points-of-view until John (the Baptist) arrives and announces the coming of Someone who will show them another way.”

Five weeks later, Schwartz delivered on both his promise and his score. “And,” says Schwartz of Lansbury and his producing partners Joseph Beruh and Stuart Duncan, “they had the faith to leave us alone.” Perhaps they were just too busy raising money. Only about half the $40,000 budget was in place, but somehow they managed to open.

En route, Tebelak and Schwartz didn’t always see eye-to-eye. While the writer-director was steeped in Peter Brook, Schwartz was a Broadway baby who knew more about PETER PAN. There were times when Tebelak feared that the show was becoming too commercial. But, as original “Day by Day” singer Robin Lamont says, “Probably neither John nor Stephen could have done it alone.”

Schwartz did fully buy into Tebelak’s concept of showing a very different side of Jesus – just as decades later he would be intent on showing a very different side of the so-called Wicked Witch of the West.

What says a great deal about Schwartz is his not asking that “By My Side” be thrown aside, as so many songwriters would have insisted. He fully admits that if he had to write a song for that spot, he wouldn’t have done any better.

When the cast members heard Schwartz’ score for the first time, they were inclined to agree wholeheartedly. As hard as this may be for us to believe, de Giere reports that most of the performers didn’t like the new music and lyrics. The musicians Schwartz approached about playing the show doubted as much as the Biblical Thomas, too.

The Original Toronto Cast of Godspell

The Original Toronto Cast of Godspell

They eventually came around, long before they got the chance to record the album. One cut from it, “Day by Day,” was released as a single and charted. By this time, the Baby Boomers and those even younger thought “show music” was of their parents’ generation, so to keep them from knowing the song came from a musical, the illusion was created that “Day by Day” had been recorded by a group that called itself “Godspell.” It was no weirder a name than such then-popular groups as Three Dog Night, Fuzz or The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.

The show was markedly different in another respect: it had no choreographer. The cast members made up moves as they went along. They didn’t get anything extra for that, but had to settle for a $50-a-week paycheck. They should have got more just for hazard pay, for the Cherry Lane Theatre would never pass for a place on Cherry Tree Lane; the place was rat-infested. (Never mind Jesus; they could have used the Pied Piper of Hamelin.)

So much was improvised that there was no official script. One day stage manager Nina Faso sat down with a typist and just called out the show to him. He was, incidentally, future Oscar-winner Dean (“Fame”) Pitchford.

Whatever was on stage, however, was working. Even the venerable Helen Hayes came to see Godspell and took a picture with the cast. Attending with a much different agenda were two songwriters who had written a concept album on much the same subject and were planning a Broadway version of it in the fall: Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice of Jesus Christ Superstar fame. They left mollified that nothing of theirs had been pilfered.

The 2012 Godspell Revival Cast (Photo: Jeremy Daniels)

The 2012 Godspell Revival Cast (Photo: Jeremy Daniels)

While all of them saw the show in New York, they could have seen it in a multitude of cities, for companies were springing up quite quickly. No regional company precisely replicated the off-Broadway script. The Boston troupe, for example, threw in a line about Filene’s Basement, the famous clothing outlet.

Alas, Tebelak died in 1985 at the mere age of thirty-five. One wonders what else he could have accomplished had he not fallen ill to alcoholism and other diseases.

That leaves Schwartz to tell us what makes a good Godspell. He insists that “A group of disparate people must come together and make a community. If this basic dramatic arc is not achieved, Godspell does not exist.” What’s worse, he says, is when “the ten performers degenerate into ten stand-up comics.” He also dislikes productions that have “Jesus portrayed too reverentially, standing off to the sidelines and watching beatifically as the rest of the cast clowns around.”

And, as de Giere reports, Music Theatre International “allows performing groups to improvise and invent new comedy lines and staging, but expects the groups will use good taste and follow guidelines.”

This is relevant, for forty-one companies around the world will present Godspell in the next thirteen months. De Giere’s book may well spur more – including one from your group.

The Godspell Experience is available at Amazon.com, Drama Book Shop, and from the book website www.thegodspellexperience.com.

Enter here to win a FREE signed copy of The Godspell Experience.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.