Filichia's Features: The 58th Anniversary of 1957-58’s Greatest Hit: The Music Man

Filichia's Features: The 58th Anniversary of 1957-58’s Greatest Hit: The Music Man

All right, it’s not Disney World, or even Disneyland. But Mason City, Iowa does have a modest theme park that celebrates its most famous citizen: Meredith Willson.

Fifty-eight years ago this week – on Dec. 19, 1957, to be precise –Willson surprised all of Broadway with his smash-hit called The Music Man.

So if you head to Mason City – the town Willson had in mind when creating River City, Iowa -- you’ll find a genuine “Music Man Square” with a statue of Willson out front and his boyhood home to the left.

Behind them is a little museum. It also contains is a mock-up of a billiards’ parlor replete with pool table. When I visited, the place was empty. Guess all the boys were out playing with the band instead.

Its gift shop celebrates two other Willson musicals: The Unsinkable Molly Brown (via a biography of this Titanic survivor) and Here’s Love (sheet music from his 1963 musicalization of Miracle On 34th Street, which the show has since been retitled).

Alas, neither here nor in the museum itself is there any mention of 1491, which opened in 1969, the same year as 1776, but was 86’d in San Francisco and never braved Broadway. At the museum, there’s not even a photo of John Cullum as Columbus.

But of course most of the gift shop is dedicated to The Music Man, so esteemed that it even beat out West Side Story for the Best Musical Tony. There are “Trouble in River City” T-shirts and copies of Willson’s “making-of” book called But He Doesn’t Know the Territory.

The tome tells us that Willson began writing what he then called The Silver Triangle in 1951. The plot that has con-man Harold Hill pretend to start a boys’ band, win over prim librarian Marian Paroo and her little brother Winthrop (and fall in love with both) was always there.

He was also intent on employing an unconventional song form that didn’t rely on rhymes. How well he succeeded with “Rock Island,” which may not be considered a song in that it has no real music. Traveling salesmen on a train merely speak in time to the choo-choo’s accelerating rhythm. Hill’s first song, “Ya Got Trouble,” does have a melody, but it doesn’t rhyme much. Still, it’s so smooth that it almost seems to.

Once Willson finished the show in 1953, he contacted co-producers Cy Feuer and Ernest H. Martin. Who wouldn’t, considering their track record of three hits in three tries: Where’s Charley?; Guys and Dolls and Can-Can. Willson auditioned, and the team put The Silver Triangle on their docket. They did stress, though, that their productions of the British import The Boy Friend and Silk Stockings – Cole Porter’s newest – would have to come first.

Both producers planned to do double duty on the show. Feuer (as Hal Prince would do later in his own career) would move from producer to producer-director. Martin thought Willson’s book needed work, and offered to do the fixing. And yet, although Martin thought himself the wordsmith, Feuer – who had had a genuine professional musical background -- was the one who made the suggestion “Call the show The Music Man.”

Unlike today, when a network will entertain only one live broadcast of musical each year, ‘50s TV embraced both Broadway musicals and originals and broadcast them several times a season. So Feuer and Martin offered The Music Man to TV. They were thisclose to signing a $100,000 pact with CBS – until the network demanded casting approval. Feuer and Martin weren’t the types to let anyone tell them what to do, for each was a tough cookie filled with arsenic. (George S. Kaufman once called them “Mr. Hyde and Mr. Hyde.”)

They also talked to film pioneer Jesse L. Lasky, who’d been toying with the idea of doing a film documentary on brass bands. A movie of the brassy The Music Man could complete a nice double-bill. Who knows what might have happened had Lasky not fallen ill and had to retire? In fact, a mere 24 days after The Music Man opened to raves on Broadway, he died.

Perhaps such setbacks were among the reasons why Feuer and Martin asked Willson to put aside The Music Man and provide the score for a new musical for which Norman Krasna was writing the book. “A guaranteed hit,” said Martin, who now was five-for-five, for The Boy Friend and Silk Stockings had opened and were already in the black.

Willson said no, so Feuer and Martin dropped The Music Man to pour their energies into the other musical: the notorious and oft-ridiculed Whoop-Up.

(A personal note: as a teen, after I’d heard about 50 other cast albums, I happened onto Whoop-Up. It was the first one to make me say, “Oh! They’re NOT all wonderful!”)

So Willson called Kermit Bloomgarden, who’d produced Death of a Salesman, The Crucible and The Diary of Anne Frank – and had recently opened Frank Loesser’s The Most Happy Fella. He auditioned the show for him and its musical director Herbert Greene at the latter’s apartment at midnight, after Greene had conducted a Fella performance. Greene showed the greater enthusiasm that night but Bloomgarden was the one to call the next day to ask, “Meredith, may I have the privilege of producing your beautiful play?”

Now that Feuer wasn’t directing, they auditioned for Moss Hart, fresh off My Fair Lady. He wouldn’t. Bob Fosse complained that “all the songs sounded alike.” But Morton Da Costa, who’d just done Auntie Mame, loved it and took the job.

Greene, who’d signed on as co-producer, had a mountain of possibilities for Hill: Milton Berle, Art Carney, Bing Crosby, Jackie Gleason (if he’d lose enough weight to be a convincing romantic lead) and Bert Parks (who would, ironically enough, play it on Broadway some years later).

They all said no, just as Gene Kelly did -- but at least he returned Feuer and Martin’s phone calls, which is more than we can say for Phil Harris – who was more gracious than Dan Dailey, who stood them up. Danny Kaye’s wife Sylvia, who made the decisions in the Kaye family, liked “Ya Got Trouble” but felt the show was not right for her husband.

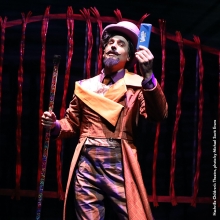

DaCosta quietly made a different suggestion: Robert Preston, a veteran of seven Broadway plays, yes, but nary a musical, and a perennial second-lead in films. That met with silence, so the script and score were sent to other luminaries: Lloyd Bridges, Van Heflin, Laurence Olivier, Alec Guinness, James Whitmore, James Cagney and Andy Griffith.

Still, they brought in Preston, gave him “Ya Got Trouble” to learn. Once they heard him do it, that was that. And while they were gambling, they signed Onna White, heretofore Michael Kidd’s assistant, in her first-ever chance at choreography.

Many were resisting the way Winthrop was characterized, however. This element was so important to Willson that he enlisted the help of Franklin Lacey, who made his living teaching spastic children.

And yet, the solution was finally found by happenstance. During “Wells Fargo Wagon,” Willson always had a little boy step out of the ensemble and lisp out some of the lyrics. Once Willson realized the lisper could be Winthrop, he replaced the bigger affliction with this lesser one.

Finding someone to play him wasn’t easy. After many auditions, Willson’s wife, while watching the TV game show “Name That Tune,” enjoyed young contestant Eddie Hodges. The kid was lucky that he won enough times to return each week, for in those days when we didn’t have the ability to record programs, more appearances were needed so that everyone on the creative team could tune in and see him. They all agreed he was worth calling in, and when Hodges arrived to audition, everyone was delighted to see that the lad had a shock of little-boyish red hair. (“Name That Tune,” like virtually every other show on the air in 1957, wasn’t broadcast in color.)

“Lida Rose” went in just before the company left for Philadelphia. For one performance, a traveling salesman sang a second-act reprise of “Ya Got Trouble” to Harold. “The Sadder-but-Wiser Girl” was originally written in counterpoint to “My White Knight,” but putting the two together didn’t sound as well as everybody had hoped, so they were split into two separate entities. “Iowa Stubborn” wasn’t going over, so Willson wrote “Blessings,” which made everyone appreciate “Iowa Stubborn” more.

Hill’s plea to Marian -- “I’ve Already Started In (to try to figure out a way to go to work to try to get you)” – was cut, but Willson didn’t give up on it; three years later, he reworked it as “I’ve Already Started In (to try to figure out exactly how to go about to get you.)”

The Philadelphia reviews were good – only to be bettered when The Music Man majestically opened at the Majestic -- one year to the day of that first audition for Bloomgarden and Greene. (Ah, when a year was all that was needed to get a show to Broadway!) “Glows with enjoyment.” (Times); “One of the few great musical comedies of the last 26 years.” (News); “What a solid hit!” (Mirror); “A whopping hit.” (Journal American); “Irresistible.” (Herald Tribune); “A knockout.” (World-Telegram & Sun).

The one thing Willson doesn’t mention is something you’ll discover if you visit “The Music Man Square.” Right across the street from Willson’s boyhood home is The Mason City Library. Could this have been where he got the idea for Marian the Librarian?

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com, Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.