Filichia's Features: Pippin Still Has Some Magic to Do

Filichia's Features: Pippin Still Has Some Magic to Do

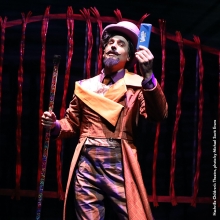

Here at the Menier Chocolate Factory in London, a word has been changed in the opening number of Pippin.

Originally in 1972, when the show’s emcee – called The Leading Player – sang “Magic to Do,” he proclaimed that he and his troupe had “miracle plays to play.” Indeed, there were some miracles in the play, thanks to Bob Fosse’s eye-popping production, Stephen Schwartz’s excellent score and, yes, even Roger O. Hirson’s book.

The three told the story of Pippin, the young medieval son of a powerful man: Charlemagne, often cited as the first Holy Roman Emperor. The lad may have lived more than 1,200 years ago, but growing up in the shadow of a great man wasn’t easy. What’s more, he endured the same problem that many teens today face: where do I fit in? Or, as John Rubinstein’s Pippin sang in one of Schwartz’s most famous songs, “Gotta find my corner of the sky.”

Before Pippin sings in Mitch Sebastian’s new production, however, Matt Rawle and his chorus members sing that they have "miracle games to play."

The reason may not be that the miracle play, a major form of entertainment between the 10th and 16th centuries, was really religious in nature. “Miracle games” may have been chosen because there’s a good deal of games-playing in Sebastian’s revival -- specifically video games that are projected on the back wall of the small stage.

The new concept will undoubtedly inspire some directors who are planning or considering new productions of Pippin. They could hire a techie or two who'd be delightfully challenged by the thought of providing CGI for a theatrical production. Think of all that technology that wasn’t around when the show opened – down to all those eerie sci-fi sounds that often accompany such games.

A case in point is the nifty illusion that occurs after The Leading Player starts to exit through a door. Before he completely closes it, we can see from his body language that he will soon start walking toward his right. Once the door is closed and he’s out of our sight behind the wall, we see a computer generated image of him walking to his right on wall’s exterior.

Similarly, Pippin (the excellent Harry Hepple) picks up an épée to fight a duel, but this time, his adversary is a computer generated swordsman. No stage blood is needed when Pippin slays him; the CGI takes care of that.

When a new character enters, the video game imagery continues (Accessing: Charlemagne). Video itself is used for Pippin’s speeches, as if they’re being broadcast to the nation. In "With You," Pippin sings to video images of women, a la J-Date and Skype.

That a fierce battle is designed as a video game could be construed as a comment on the puerile aspect of waging war in the first place. But the ultimate reason must be economic: creating an army from computer graphics is less expensive than hiring an army of actors.

Of course, since Pippin’s out-of-town tryout in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1972, audiences have adored becoming part of “No Time at All.” It’s the show-stopper sung by Berthe, Pippin’s grandmother, who gives him the advice that even at his young age, “it’s time to start livin’.”

What originally made the number extra-special is that Fosse flew in a large piece of parchment with Gregorian chant on music staffs and lyrics below them. As a bouncing ball caressed each note, the audience got to sing along with the penultimate chorus.

Audiences have always had glorious times with the song, and here the crowd has equally as much fun with it. For those who complain that for the last 40 years that there hasn't been "a tune you can hum" in Broadway musicals, "No Time at All" proves them dead wrong. In the eight Pippin audiences I’ve encountered in the last four decades, every crowd has no trouble learning the song after only one hearing.

Here the lyrics are simply projected on the back wall. But seeing them allows us to realize that Schwartz was inadvertently prescient in this song. He wrote that "sages tweet." These days, they certainly do -- along with everyone else.

Actually, Pippin does some contemporary tweeting of his own when outlining his plans for the kingdom. His sentiments, including that "People should have the right to speak out freely," are projected on the wall in fewer than 140 characters.

Still, Pippin doesn't have the confidence of his people. When the chorus members say, "Long live the King," they say the first three words enthusiastically enough, but adopt a purposely dull tone for "king." Nevertheless, Pippin, after showing generosity to his subjects, cocks his crown at a jaunty angle; he's comfortable in his new role.

Not for long. One of the valuable lessons that Pippin teaches is that being in charge isn't easy. While we all feel free to criticize (if not excoriate) our politicians, Pippin reminds us that we don't know the half -- nay, tenth -- of what’s going on.

No wonder that Pippin retreats into suburbia with single mother Catherine and his son Theo. While Theo in the original production was played by a grammar school-aged kid, here he’s played by a diminutive twentysomething. The point is still made that young people of all ages can profit from parental guidance.

Granted, the younger the child, the more devastated he will be when his pet duck dies. But the more important point is still made: Pippin becomes Theo’s surrogate duck -- and Theo becomes Pippin’s surrogate son. When Theo later gives him a gift and Pippin is greatly moved by it, the lad gives a what's-the-big-deal shrug. But we know and he knows that he has genuinely come to love Pippin.

And yet, at the end of the show in a scene that wasn’t part of the original (but one of which Schwartz has become quite fond), Theo sings "Corner of the Sky" before he leaves home to encounter new adventures. All kids must endure wanderlust and confusion before finding themselves.

Hirson's book has often endured criticism, but that has never kept it from saying something important: that a man can seek to succeed at sex, power, painting and military adventures, but in the end he may well find that he’ll be most sustained and rewarded if he raises and loves a child. No wonder that when Pippin’s original Broadway production closed in 1977, only seven musicals had ever run longer. Women had to appreciate the message that that the love of a good woman is worth its weight in platinum; men who had had trouble committing to love and marriage might have seen new worth in a settled-down lifestyle.

As a result, Pippin, 40 years on, still holds great value – even if you do it without a single computer graphic.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His newest book, Broadway MVPs: 1960-2010 - The Most Valuable Players of the Past 50 Seasons, is now available through Applause Books and at www.amazon.com.