Filichia Features: The Sun Comes Out On Annie Jr.

Filichia Features: The Sun Comes Out On Annie Jr.

How long have I been attending community theater productions? Let’s put it this way: when I started, Betty White could have still given birth.

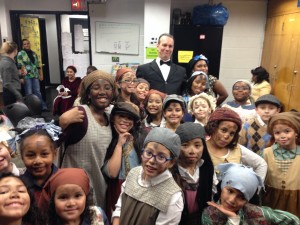

And yet, here at the Bronx House, I’m seeing something that I’ve never witnessed before in hundreds of trips to basements, churches, auditoriums, cafetoriums, black boxes or genuine theaters. Derek Woods, the executive director of Riverdale Children’s Theatre, has an idea that is well-worth knowing and borrowing.

Woods is an Emmy-nominated videographer, too, and he put those talents to great use with Annie JR. As the overture plays, he shows in black-and-white film movie-like credits on the back wall. First, he gives credit where credit was due -- to bookwriter Thomas Meehan, composer Charles Strouse, lyricist Martin Charnin and director-choreographer Katy Baker.

But then – but then -- Woods smartly puts on the screen the 37 names of each and every member of the cast. The result? Before the show even begins, parents and friends are cheering as they spy the names of the kids they came to see, now prominently emblazoned and celebrated.

I suggest that every community theater do this, for it immediately gets the crowd in a happy and receptive mood. For Annie JR., it’s particularly apt, for listing an entire cast by name was a convention of movies in the thirties – the time in which this musical takes place.

Of course, if the production that follows stinks, the audience’s good feeling will melt quicker than Frosty the Snowman in Mrs. Lovett’s oven. But from the outset, no one need worry, for even before the lights come up, we see on the dimly lit stage that dozens of girls confidently march on and pose in a way that shows that they’re proud, prepared and ready to perform.

As Baker will later tell me, “The partnership between the Riverdale Children's Theatre and the Bronx House is really positive for both groups. This is an area of the city where many kids may not otherwise have an experience like this one. This program is very demanding and we strive for professionalism, but both organizations are committed to keeping things affordable. No one is excluded because of a family's particular socioeconomic status.”

When the lights come up, we see in the girls’ faces seriousness worthy of Gulag prisoners. That the Bronx House stage is small actually helps, for having many girls spill over and onto each other suggests the cramped and oppressive conditions that many orphans have endured.

All right, but what about when Oliver Warbucks’ mansion is called for? Ah, once again Woods comes through with projections, deftly having the dull orphanage bleed into the posh surroundings.

Woods also makes a wise and innovative lighting decision during Miss Hannigan’s complaint about “Little Girls.” Midway through the number, he suddenly and completely bathes the stage in red. It suggests that Hannigan would like to start a Reign of Terror on the kids that would make the one enacted during the French Revolution seem like a playground spat.

And when Warbucks, Grace and Annie get inside the Roxy and start watching the movie, Woods shows a scene from King Kong -- which indeed was released in 1933, when Annie JR. takes place.

As Annie, Kiki Manuguerra’s turned-down mouth shows long-time suffering. But this kid can come alive at the mere prospect of good news. When Annie wants to impress Grace Farrell that she’s smart, she spells “Mississippi” as evidence of her vast knowledge. (Indeed, that was the benchmark of a kid’s intelligence back then.) Manuguerra begins confidently, yes, but just before she gets to “P-P-I,” she raises a finger as if to say “I’ve conquered the first part of the word, but I know there’s an even more difficult part to come, but I’m ready for it.”

Later, in “I Don’t Need Anything but You,” when Manuguerra reaches the lyric, “Yesterday was plain awful,” she melodramatically raises an arm to her forehead, but when she gets to “That’s then,” she takes that arm and makes a furious thrust that shows she’s indeed put her past behind her.

Annie JR is of course a good-time musical, but it does serve to teach its performers and audiences a message worth learning: “Be careful what you wish for.” Throughout the show, Annie wants to find her birth parents, and even the prospect of having a billionaire adopt her can’t compensate for her blood relatives. But later in the show when her (alleged) parents show up, she realizes that her real parent is the one who’s been caring for her: Oliver Warbucks, who’s certainly earned the name Daddy. Annie, after a lifetime of wanting to find her true father and mother, now sees them as an unknown quantity and people to be feared. But this leads to another moment where Manuguerra proves extraordinary: when she’s asked if she’s ready to go with these strangers, the way she staunchly says “Yes” proves that she’s prepared to make the best of a bad situation and she long ago became brave about the cards that fate has always dealt her.

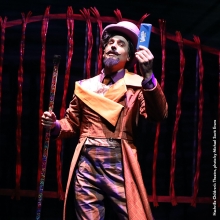

What’s always fun in any children’s theater production is seeing kids who show great potential. While I can’t identify by name one little girl, I can see that she’s going to make a sensational Annie in a few years. Meanwhile as Rooster, Daniel Mejil is already a marvel. Some kids are simply born with the musical theater gene, and Mejil is one. He makes each dance move crisp and gives a definitive head nod as the last note of “Easy Street” blares. And as if his suave steps during a song aren’t enough, when he pretends to be Annie’s father, he (and Kaylani Mendoza’s Lily) adopt Southern accents that are pin-point perfect.

Baker gives a reason why everyone’s performance is so stellar: “With special permission from MTI, Riverdale used two teaching artists: Christina Pagan for Miss Hannigan and Guy Ventoliere for Daddy Warbucks,” she says. “They’re professional actors who aren’t just great with kids; they were a huge support because they helped teach, block, hang lights, build the set, facilitate scene changes and aided classroom management. For young actors to have professional actors with them was very special. This allowed them to gain an understanding of the right way to share a scene on stage.”

Sharing is something that Riverdale must do with Bronx House. “There’s quite an upheaval here for a couple of weeks,” says executive director Howard Martin. “Bronx House services about 1,200 people a day, what with the senior center and after-school programs, so giving up this space means a lot of maneuvering around.” His face then lights up. “But it’s all worth it. I love coming to auditions and seeing what’s going on, but then I don’t come until the performance and I’m blown away by all that Derek and Katy accomplish.”

“I grew up in the Bronx,” Woods says, “when there were so many programs like this. Now they’re all gone. My wife Becky Lillie-Woods and I were not going to stand for that. She became the artistic director of our organization, which now has about 150 kids in our program. We rehearsed this show for three months, two to three times a week -- and look at the results.”

Says Baker, “My mantra throughout this experience has been ‘It’s about the process, not the product.’ When you really focus on each child's process, the product is almost never a let-down. For many, this was their first theatrical experience, their first time in a body mic or a wig. Having a cast of almost all young children adds a lot more responsibility; a director must also be a child-care provider and a teacher. In any given rehearsal, I was wiping noses, tying shoes and bandaging boo-boos -- but by the time we opened, the kids understood the dramaturgy of the show and had improved their theatrical literacy.”

Baker’s finest moment may well be a sequence during “N.Y.C.” To create the hustle and bustle of Manhattan, she has some kids mime riding and strap-hanging on the subway. But she doesn’t stop there. Baker has instructed one kid to pretend to be checking the racing form and making his decision on what horse to play; she has another anxiously consulting her watch to see if the train will get her to work on time; and she has yet another simply reading. Baker, like the best directors, knows enough to make every ensemble member a distinct character.

“Giving each kid at least one moment to shine is a vital component in a children’s theater production,” says Baker. “It was important to me that the kids’ parents got to be impressed by something their child did on stage.”

And that, of course, is even more rewarding than getting an on-screen credit at the beginning of the show.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com.