Filichia Features: Murder Ballad Will Out

Filichia Features: Murder Ballad Will Out

Whodunnit?

One thing’s for certain: in the musical Murder Ballad, the butler didn’t.

He couldn’t have, for none of the characters in this 2012 musical works in that capacity. Michael is a poet. Tom is an actor/bartender -- with the accent on the last three syllables.

Because Sara and The Narrator are both women, they couldn’t be butlers -- maids, yes, but bookwriter-lyricist Julia Jordan hasn’t put them in domestic service. Both women are maids only in the sense that they’re unmarried young women in their twenties. Sara’s goal is to be a successful songwriter and the Narrator – well, we’ll find out more about her much later.

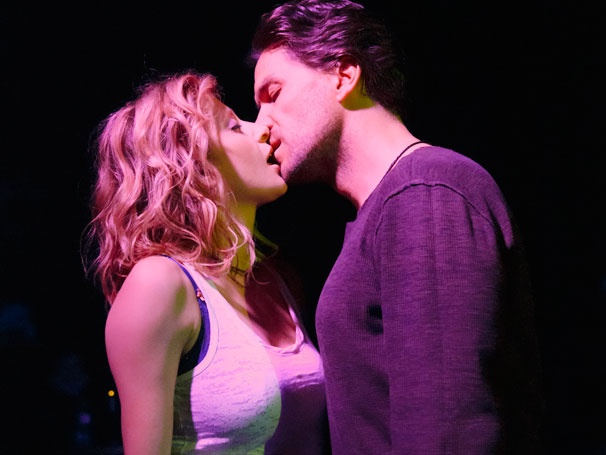

This is a “beautiful people musical,” one for which you must have three startlingly alluring performers. Sara, Tom and Narrator must be knockouts, while Michael’s looks are far less important. He mustn’t be unappealing, but a middle-of-the-road appearance would be right.

Make certain their voices are strong and capable of much wear and tear. They’ll have to sing indie rock star Juliana Nash’s stirring and vibrant music. Yes, they only need to sing it for ninety minutes, but the show is intermissionless, so there’s goes any chance for even 10 minutes of R&R. (That’s rest and relaxation, not rock ‘n’ roll.)

If you have a fetching and talented young woman in your company who often wears a “But What I Really Want to Do is Direct” T-shirt, cast her as the Narrator. In a sense, she functions as a director, often blatantly telling the three other performers where to stand and what to do.

Are there any Narrators in musical theater history who drink as much as this one and become as intoxicated? Narrator’s imbibing is important to the plot and it shows that the ol’ Roman belief that “In vino veritas” – “In wine, there is truth” -- hasn’t yet found an expiration date. No wonder the whole show is set in a bar.

“Someone’s gonna die,” Narrator reveals in the show’s sixth line. But which of the three? Did you think Narrator would make it easy for you?

Sara sings “We all want to touch the flames, but not get burned.” No, the victim certainly doesn’t see the murder coming, but don’t young people tend to think that they’re invulnerable and immune to all dangers?

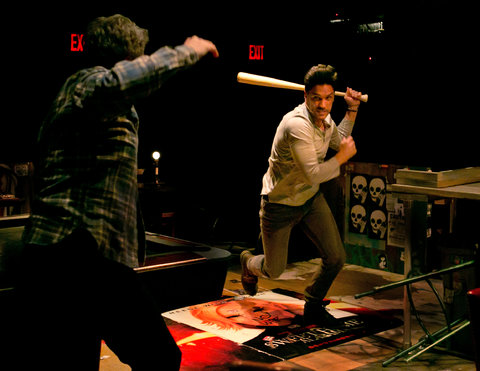

“A King, a Queen, a Knave and a club,” sings Narrator. She casts Michael as the King, Sara as Queen and Tom as the Knave. The club? Well, yes, a nightclub is germane to the plot, but don’t ignore that baseball bat in the corner. Not only must you have one on hand, but it also cannot be one of those hollow aluminum jobs. Solid wood is required for the plot.

Narrator introduces us to Sara, the budding singer and Tom, the budding actor. But this budding isn’t for you, Sara or Tom. After the early happy days in which they “drank each other’s secrets in,” they eventually swallow the bitter taste of failure: his own, her own and each other’s.

Sara, because of her failures, finds herself having a greater need to be loved and turns to Tom for a solid commitment. Tom instead needs to get away from the woman who once believed in him but has seen him flop. Knowing that she could list his every failure in chronological order is no aphrodisiac. He wants to find someone new who can give him a clean start on a clean slate.

At the top, however, your Sara and Tom must have dynamic chemistry, for they are certainly written as sexual soulmates. Sara must display an especially robust libido, for after she leaves Tom, goes on a drinking spree and bumps into Michael, she’s blatant about wanting to bed him.

Those who have Ph.Ds in poetry aren’t usually portrayed as street smart, but Michael is savvy enough to infer that she’s experienced a just-broken-off relationship. “Bad boys?” he asks rhetorically. “They don’t stay.”

Michael is instead a good man, but don’t direct him as a fool. He’s a sincere soul who eventually marries Sara. Meanwhile, Tom is merely making Tom Collins’ and other assorted drinks for an upscale bar crowd. And yet, Tom isn’t beaten down, but now has a goal of opening his own club. Falling in love is no longer important.

We never meet Michael and Sara’s new daughter Francesca, but she’s important to the plot. “A baby changes everything,” the couple acknowledges, so Michael will now “put the poetry away; study hard for his MBA.” Thus, the actor you cast as Michael must convey that he’s proud at the thought of becoming a better father and husband.

Kids grow up faster, however, and Francesca reaches her fifth birthday in a mere seven lines of narration.

During that short stretch, however, your Sara must begin to show the frustration of still being strikingly beautiful and youthful while weighed down with maternal responsibilities. Have her convey an attitude of “Where did it all go?” even before she reads in the papers that Tom now owns a trendy club and decides to give him a call.

Now the suddenly affluent Tom has time for love. Although Sara is “petrified, I am – and I’m not wood or clay,” she begins an affair with Tom. To the surprise of many in the audience, she eventually chooses Michael. “We’re always gonna want for something,” she says, resigned to her fate.

But Tom won’t go quietly. He plans to murder Michael, who has learned about the affair and in turns plans to murder Tom. And because Tom won’t give up on Sara, she considers murdering him, too. And that’s when the bat comes out.

All murder mysteries need to have a surprise ending. The one here is that “The Narrator Did It.” She tells us that she had a relationship with Tom, and once she saw how involved he was with Sara, she took bat to hand and – well, went batty.

Now in any murder mystery, once the crime is solved, everyone in the audience should be swatting his forehead with the palm of his hand and saying, “Awwwww! I shoulda seen that coming! They gave me the important clue, and I was too dumb to notice! What a marvelous and clever solution that got past me!”

This musical doesn’t bestow that on its audience. As a result, what your Narrator must do is seem increasingly guilty as she becomes increasingly lubricated. Direct her so that she seems to be telling more than she’d originally anticipated. By the end, see that she’s virtually given a police-station confession.

Murder Ballad was first produced in the cozy confines of the Manhattan Theatre Club, where audiences almost felt as if they were at a bar. Then eight producers decided to bring it to a downtown theatre for a commercial off-Broadway run. They stripped the large theater of most of the conventional seating and replaced it with tables to make a gigantic restaurant.

The little show got lost because the director opted for environmental staging (where scenes are placed here, there and everywhere). Spectators were constantly turning their necks to someplace new, and often found that the action was so far away that they couldn’t make out what they were supposed to see. Add to that that Murder Ballad's story is a small one, and the result was a run of two months.

Moral of the story? Start looking around for a restaurant that has a small function room with a genuine bar in it. Many restaurants have such spaces which are used for daytime meetings but are often empty at night. Stage the show near the bar, and have all the tables face the stage. Ragtime says “Make them hear you,” but where Murder Ballad is concerned, “Make them see it,” too.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.