Filichia Features: John & Jen & John

Filichia Features: John & Jen & John

By Peter Filichia on February 27, 2015

in

Making Theater, Show/Author Spotlight

| Tags:

Filichia Features, John & Jen

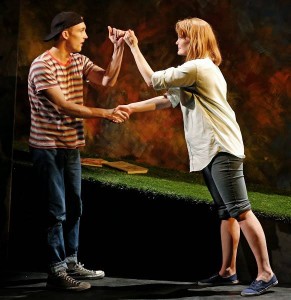

Conor Ryan and Kate Baldwin. Photo by Carol Rosegg.

Here’s what I’ve observed about brothers and sisters.

They fight like mad when they’re young, but as time goes by, they start to see the other’s virtues. That leads to their truly loving each other.

What makes John & Jen a more compelling musical than most is that it shows the opposite scenario.

The 1995 off-Broadway two-hander – now getting a fine revival at the Keen Company – has a book by the show’s lyricist (Tom Greenwald) and its composer (Andrew Lippa). They start their story in 1952, when early Baby Boomer Jen, now six, welcomes her baby brother John into the world. Because their own mother is preoccupied by an abusive husband, Jen soon becomes a virtual mother to Jon.

The man is an abusive father, too. And yet, as the years go on, no matter how much Dad beats John, his son finds a way to rationalize the bully’s behavior. “I deserve it,” he sings. “It’s for my own good. He’s big and strong and never wrong.”

Anyone who’s interested in playing John should get to Theatre Row and see how Conor Ryan accomplishes this difficult scene. Just from the way he flashes his eyes, he conveys the attitude of “I know I’m right.”

Jen knows better. She’s the one who must explain why Santa didn’t come this Christmas. Similarly, anyone who’s intent on playing Jen should also see how Kate Baldwin conquers this scene with ease. Before she gets down to explaining the so-called realities of Santa Claus, she licks her lips in a let’s-get-down-to-business demeanor and then plows on.

Greenwald and Lippa reiterate that the child of abused parents tends to become abusive himself. What wise advice they have Jen give her baseball-crazy brother: “When you want to hit something, hit a home run. When you want to throw something, throw someone out.” Those are words that many parents should pass on to their children.

One wonders how much rehearsal time went into the elaborate handshake director Jonathan Silverstein has Baldwin and Ryan do. It’s one of those slap-hands-high, slap-hands-low, touch-your-elbows type of maneuver that kids love to do. Audiences always take to it as well, and the crowd at Keen cooed in appreciation of the skill and practice that went into it. Do allow extra rehearsal time so your performers’ handshake is equally complicated and effective.

As detailed as the handshake is, it didn’t represent the greatest challenge for Baldwin and Ryan. Playing a kid is a dicey assignment for any actor, for there’s the temptation to overdo the high-pitched, simplistic voice. All too often, an actor comes across sounding as if the child left his brains at the playground.

Silverstein has ensured that both Baldwin and Ryan don’t. They sound young, yes, but nevertheless natural, and that’s one of the production’s finest achievements. Make certain that when you do the show that it’s one of yours, too.

Halfway through the first act, Baldwin gets to drop the childish tone, when 1964 high school graduate Jen is ready to go away to college. The actress beautifully conveys the blithe attitude Jen must adopt in hopes that she can make John believe life won’t be so hard without her. Watch how skillful Ryan is here at wanting to seem brave while being very frightened underneath. He then eases into another attitude: Dad will still be here when Jen is not, so he’s the one I have to please.

So just when the show threatens to get too sentimental, we see a rift between brother and sister. They grow apart, because to Jen the excitement of New York City doesn’t only mean sex (with a young unseen man named Jason), drugs and rock ‘n’ roll; it also involves liberal politics and bra-shedding. “We believe in love” Jen sings about her relationship with Jason, and Lippa gives Jen a beautiful note to sing on the word “love.” Baldwin, one of our strongest of the current crop of musical theater actresses, gets the most out of it.

So John comes to hate Jason, whom he dubs as “too yellow to face the red tide” of Communism in Vietnam. Yes, now that Jen has distanced John, he’s more intent on becoming his father’s macho alter-ego. What better way to show his devotion than to fight in Vietnam? “I’ll make him proud of me,” John says staunchly.

As a result, those staging John & Jen will also need a large American flag to place on either the floor (as Silverstein does here) or on a genuine casket.

The musical is not over. We have a second act to go, and it’s not all Jen. She now has a son whom she’s named John in honor of the brother she still mourns. Of course, he’s played by the same actor we met in Act One. Ryan is able to create a new character while also retaining a bit of his uncle in him.

Jen wishes that he had more. There’s the rub: she wants him to be his uncle – at least the uncle that she fondly remembers, with all the qualities she loved and, of course, with none that she didn’t like.

Greenwald and Lippa thus introduce another worthy theme. Can’t we accept our children for what they are and not force them into templates that hold no interest for them?

It’s all symbolized when John wants a baseball glove, and Jen gives him the one his uncle used. She, of course, assumes he’s going to be thrilled at this heirloom, but all the lad can see is a second-hand antique. Both are disappointed in each other, and certainly not for the last time. Still, Jen vows to her dead brother “I won’t fail my son the way I failed you.” It’s a reminder that those who lose loved ones in war have their own form of post-traumatic stress disorder, too.

History will repeat itself -- not only because John wants to leave home and go to New York, but also because Jen becomes so frustrated by her son that she hits him. It’s a sobering reminder that the sins of the father are handed down to daughters as well as sons. As another more famous musical has taught us, “Children can only go from something you love to something you lose.”

This is not a show to schedule for Father’s Day. Jason turns out to be almost as much of a lemon as John and Jen’s father was; he’s mired in the ‘60s, bolted and is apparently still off trying to “find himself.”

Just when Greenwald and Lippa seem to be painting themselves into a doleful corner, they’re able to imbue their characters with strength and nobility. At show’s end, John & Jen find the common ground that love has made a solid foundation.

It’s an easy show for props. A few stuffed animals, a suitcase, some baseball equipment (glove, bat and plastic batting helmet) and you’re pretty much in business. As for costumes, a search through the average closet will give you almost everything you need. The only exceptions are a baseball uniform, a sailor suit and – here’s the toughie -- adult-sized “onesies” pajamas for both performers .

John & Jen is a nice show for community theater. And how about casting an adult brother and sister? (Well, providing that they get along, of course.)

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available for pre-order at www.amazon.com.