Filichia Features: God Bless God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

Filichia Features: God Bless God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

Now that the Summer of 2016 is coming to an end, let’s recall one of the season’s theatrical highlights: God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater.

In July, New York City Center’s Encores! Off-Center series revived the 1979 off-Broadway musical written by the then-unknown composer Alan Menken and the equally obscure bookwriter-lyricist Howard Ashman (with a little help from their friend: lyricist Dennis Green).

Menken and Ashman would go on to write many a fresh take on fairy tales: The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, of course. But in a way, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is a fairy tale, too, because, in keeping with Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s 1965 novel, it deals with a rich Indiana multi-millionaire who just loves giving away his money to poor, downtrodden people. All a townie would need to do is call Eliot Rosewater, tell him what he or she needs -- and a check is almost in the mail. Eliot may well believe that charity begins at home, but he doesn’t think that it must stay there.

Few people know Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part II, and fewer still know its character Dick the Butcher. And yet, most of us have heard what Dick says in Act IV, Scene II: “The first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers.”

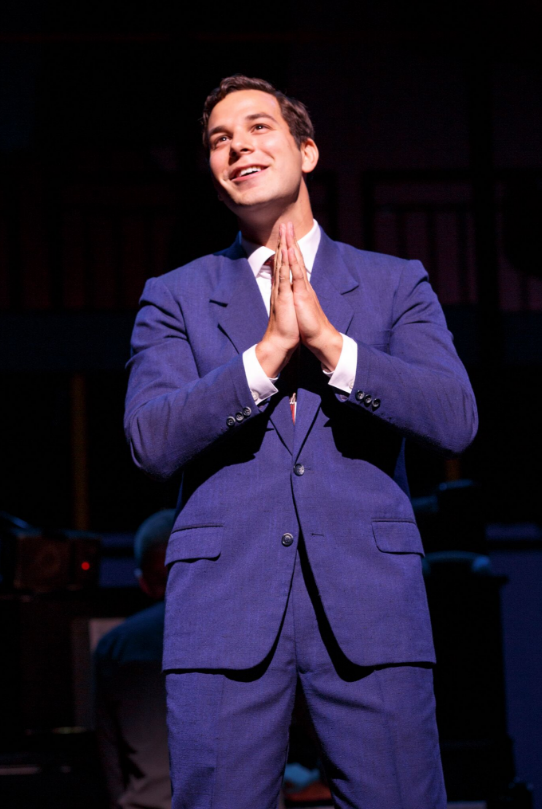

Skylar Astin in New York City Center's production of Kurt Vonnegut's God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (Photo by Joan Marcus).

We certainly want to follow his advice after we meet Norman Mushari, Esq. He’ll make Eliot seem incompetent for throwing away his money on (his opinion) the very undeserving poor. But examine his motive: “In every big transaction, there’s a magic moment when a man who’s entitled to a treasure has not yet received it. An alert lawyer will make the moment his own, possessing the treasure for a magic microsecond, taking a little of it, passing it on. If the recipient of the treasure has an inferiority complex and feelings of guilt, the lawyer can often take as much as half the bundle and still receive the recipient’s blubbering thanks.”

Getting Eliot judged incompetent may not be difficult. When he and his wife Sylvia attend Aida at the Met, he can’t stay quiet during the final scene. For when Eliot sees that the two entombed lovers are singing their farewells, he yells aloud that they should stop vocalizing or they’ll use up the little air they have and will die that much quicker. If that isn’t enough, he storms the stage to save them, utterly humiliating Sylvia in the process. (And most theatergoers think they have a problem when cell phones go off!)

Under these circumstances, is there any surprise that your costume coordinator will need to find a strait-jacket? For Eliot, you assume? No – for Sylvia, whom Eliot drives crazy.

The music allows Menken to show his sophisticated side, which is a strong one. The City Center crowd laughed long and hard at both lyricists’ work. Ashman’s language is occasionally salty, but because the show was written nearly 40 years ago, it may not offend very much.

Santino Fonatana and the cast of New York City Center's production of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (Photo by Joan Marcus).

Rosewater is definitely a period piece, very 1979, and must be kept there, for many lyrics refer to people, places and things of yore. (Green gets in a good one about Johnny Carson.) One name from way-back-when received a generous laugh from the City Center crowd and is likely to get one from yours too: Alexander Hamilton.

And yet, in one sad way, Rosewater is quite au courant. In a time when citizens of Youngstown, Camden and even Cleveland are having terribly hard times, we’re reminded that some people have been written off as “obsolete” and that “America doesn’t need them anymore.” As Madame Armfeldt sings in A Little Night Music, “Let’s hope this lunacy is just a trend.”

Vonnegut describes Eliot as overweight and slovenly, and that’s how he was cast in 1979. At Encores! Santino Fontana, one of our current crop of dashing leading men, played the role. It was maverick casting from director Michael Mayer, but it showed that a director can cast a fine character man or extraordinary leading man and there’ll still be a convincing show.

Fontana was so resolute when he squared his jaw and said “I’m going to give respect to anyone who needs it.” So among the satire and the craziness, Rosewater carries with it the fine message that people need money, sure, but they need respect as well – maybe even as much.

The show has another message worth hearing: Eliot treats everyone the same, which reminds us that we should, too. Never mind who’s ostensibly “important.” Eliot feels that we all are. Besides, giving the same attitude and respect to everyone is, ironically enough, easier in the long run. You don’t have to put on different faces for different people. One size fits all. God bless you, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr, Howard Ashman, Alan Menken and Dennis Green for reminding us.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com. His book, The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.