Filichia Features: Welcome THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS

Filichia Features: Welcome THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS

Good news for theater companies.

The Scottsboro Boys is available for productions at community theaters and high schools.

The 2010 Tony-nominated musical by bookwriter David Thompson, composer John Kander and lyricist Fred Ebb received its first amateur airing at the International Thespian Festival in Lincoln, Nebraska last month.

What a hit it was. The capacity crowd mightily applauded each song and went silent when the drama became rivetingly powerful.

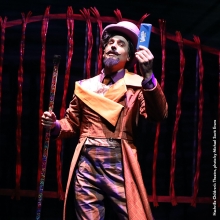

Actually, "amateur" isn't 100% accurate. Although 10 cast members hailed from Bradford High School in Kenosha, Wisconsin, three professionals played The Interlocutor, Mr. Tambo and Mr. Bones.

Some will recognize these names as characters in minstrel shows. Don't blanch: the writers had good reason for returning us to the time of this odious and racist "entertainment." Minstrel shows were still produced during the '30s when this story of nine young African-American men made front-page news.

They were traveling by train from their native Chattanooga to Memphis and minding their own business. "Commencing in Chattanooga," with Kander's pulsating melody and Ebb's joyous lyric, conveys the excitement of taking a trip for the first time. It makes us identify with and like the young men.

In a nearby car Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two prostitutes, were on the verge of getting arrested for soliciting.

Price's quick thinking saved them. She said that all nine young men had gang-raped them. "My privates which were private weren't private anymore," Ruby sings in a funny Ebb lyric. But the Lincoln audience didn't laugh. These theatergoers knew bad times were coming for the men.

All were jailed in Scottsboro, Alabama to await trial. "I'm gonna get out of here," insisted Haywood Patterson (the amazing Ben Woods), their de facto leader. Then he added with a plea of desperation: "I've gotta get out of here."

So in court he pretends to be slow-witted in hopes that will work for him. His song is called "Nothin'," to reiterate that he didn't know anything.

It turns out to be well-named for a different reason: "Nothin'" will help him.

"Nobody calls an Alabama woman a liar" argues the prosecution. In these pre-DNA days, a black man was guilty until proved innocent. After the judge handed down the death sentence, he added "May the Lord have mercy on your souls."

He most certainly did not.

Even years later, when Bates' conscience finally made her confess that she'd lied, a new jury couldn't admit that the previous jurors had been wrong. Worse, that a "Yankee Jew" had traveled to defend the nine influenced their decision.

Appeals lasted into the early '50s when the show's most potent moment occurs. Patterson is up for parole. What's been made clear to him is that he only has to admit to the crime to be set free.

This judge knew full-well that Haywood was innocent, but he needed Patterson to confess. By then releasing him, the law would seem kind and forgiving to a guilty man and that Alabama had always been unwaveringly right.

Yet even after endless years in prison -- and with the freedom he'd sought for years dangling before him -- Patterson was strong enough to tell the truth. He denied the state the satisfaction of letting everyone believe that he'd been guilty since Day One.

The reward for his honesty and courage was more prison time.

For scenery, you only need chairs with backs high enough to reach the napes of men's necks. Those backs should have see-through vertical bars so that when the men sit with their backs to us, they'll look as if they're in jail.

If casting a dozen young men seems daunting, you could mix and match genders as expert director-choreographer Christopher Carter did. Zella Weams portrayed Charles Weems when she wasn't Victoria Price just as Nick Daly played Ruby Bates when he wasn't Ozie Powell. Daly's putting a scarf around his neck turned him into a female character (as did his effective high-pitched voice).

Many of Thompson's lines pack solid punches. Even before they're accused, when a sheriff comes on the train one boy says "Take your hat off! You're talking to a white man!"

In the show's specific reality, he's not. Aside from The Interlocutor, all cast members are black (as some minstrel shows were). They play the other whites, although you'd be fine if you cared to augment your cast instead of doubling.

The Scottsboro Boys does have one role for an African-American woman. She's the first character seen and is waiting for a bus. Once she gets on it and sits, the country will change thanks to this Rosa Parks.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com . He can be heard most weeks of the year on www.broadwayradio.com.

Follow the fun @mtishows on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.