Filichia Features: Put Passion into Your Life

Filichia Features: Put Passion into Your Life

If you do Passion correctly – meaning the way that Stephen Sondheim envisioned it – your audience will applaud only once the entire night.

If you do Passion correctly – meaning the way that Stephen Sondheim envisioned it – your audience will applaud only once the entire night.

That will happen at the end of the show, after the lights have dimmed and the performers have emerged to take their bows.

Not getting applause after each song is virtually unheard of in musical theater. But for his 1993-1994 Tony-winner, Sondheim carefully calibrated how one song could easily blend and merge into another. Perhaps he felt that after all the raves and six songwriting Tonys, he didn’t need to hear any more applause.

In John Doyle’s exemplary production currently at Classic Stage Company in New York, Sondheim gets his wish: the audience is silent throughout the show. If a blindfolded passer-by were brought into CSC, he’d assume that the seats were filled with third-world country prisoners whose hands had been chopped off for various infractions.

In John Doyle’s exemplary production currently at Classic Stage Company in New York, Sondheim gets his wish: the audience is silent throughout the show. If a blindfolded passer-by were brought into CSC, he’d assume that the seats were filled with third-world country prisoners whose hands had been chopped off for various infractions.

Some artistic directors of community and high school theaters immediately dismiss Passion because its opening scene features nudity. Not anymore, for Doyle gets his lovers, Giorgio and Clara, to reflect their passion by staring into each other’s eyes. Thus, don’t assume that you need to strip your performers.

Sondheim rarely-if-ever writes in clichés, but he seems to have delivered an abundance in his opening song for Giorgio and Clara: “You are so beautiful.” “I’m so happy.” “All this happiness.” “So much love.” This from the lyricist who’s routinely delivered the unexpected – such as in A Little Night Music, when he had a man intent on seducing a woman sing “You Must Meet My Wife.” Who else but Sondheim would have thought to give a deranged barber a beautiful ballad (“Johanna”) to sing while he was cutting throats?

But Sondheim’s platitudes make a point. It’s a chemical reaction, that’s all, for both Giorgio and Clara, who are only superficially in love. The frail and yet steely Fosca will show both what wild, unmitigated love is long before its 100-minute running time has concluded.

But Sondheim’s platitudes make a point. It’s a chemical reaction, that’s all, for both Giorgio and Clara, who are only superficially in love. The frail and yet steely Fosca will show both what wild, unmitigated love is long before its 100-minute running time has concluded.

After Giorgio is transferred (to his and Clara’s chagrin), he meets his new commanding officer Colonel Ricci and his fellow soldiers. But who is that who’s upstairs screaming? Giorgio is unnerved, but the men say nothing – because that piercing and tortured voice belongs to Ricci’s cousin Fosca.

In the original production, when Fosca did decide to appear, her entrance was dynamic. Behind a scrim where we had been able to make out a staircase, we now saw the silhouette of a woman descending it. We would finally see this creature who’d been assaulting our ears.

There’s no staircase on stage at CSC. In fact, there’s no set. Indeed, the program fully admits it, for it gives no credit to a set designer. We see Fosca (Judy Kuhn) slowly and deliberately walk on from the wings. No, this entrance isn’t as dramatic as a shut-in descending a staircase, but ‘twill serve.

No set really means no set. There’s no long table at which the soldiers eat their meals, although there are chairs. Soup spoons are in evidence but bowls are not. When the soldiers play billiards, they hold cues over an invisible pool table. True, Jane Cox’s wonderful rococo lighting helps immeasurably in creating mood. But Doyle has always believed that less is more – mostly because his Watermill Theatre in England has never been able to afford even quasi-lavish productions. Still, in this era when frugal is the new cool, feel free to minimize and minimalize.

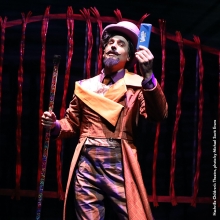

Passion won’t overtax your costume budget, either. True, there are eight soldiers who must be in period uniforms – high-waisted pants, epaulets, gold braids and the like. Still, there’s only a cast of 14, which Doyle has managed to shave to 10.

Passion won’t overtax your costume budget, either. True, there are eight soldiers who must be in period uniforms – high-waisted pants, epaulets, gold braids and the like. Still, there’s only a cast of 14, which Doyle has managed to shave to 10.

In your company, you may well have women to play Fosca’s mother and her first husband’s mistress, but on the off-chance you don’t, you could do what Doyle has here: put two actors in drag. While this may sound too frivolous for a show that’s among musical theater’s most earnest, each scene is short enough that a quick female impersonation won’t ruin the somber mood.

Doyle and Kuhn keep us guessing: is Fosca actually a hypochondriac? The text eventually says no, but there’s nothing wrong with having an audience consider that possibility.

She certainly is, however, a woman possessed. Doyle shows that when Ricci offers Fosca his arm while they walk, she’s reluctant to take it; she wants Giorgio’s. When Fosca learns that Giorgio won’t reciprocate her feelings (mostly because he already has Clara), she’s maddeningly condescending: “You may go now, Captain,” she says tartly. “I have more important things to do.” Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard states that“Great stars have great pride,” but so does this great invalid.

But like Norma, Fosca will soon swallow her pride in a series of painful lumps. When she offers Giorgio her hand to shake, she has the demeanor of a queen who’s greeting a peasant. She makes clear that she expects him to kiss it – and yet, her emotions take over and she winds up fervently kissing his hand.

The trickiest scene in Passion has always been the one in which Giorgio is on the train that will finally take him miles away from his stalker -- only to look up and see Fosca standing there in his compartment. Each time I saw Passion on Broadway, the audience derisively giggled at her sudden appearance. Try as he might, director-bookwriter James Lapine couldn’t eliminate the unwanted laugh.

Sondheim has been asked about this, and has said that the audience has the need to laugh to break the tension they've been feeling. Perhaps. But Aubrey Berg was able to short-circuit this unwelcomed laugh in his 1997 production at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music (in which, incidentally, Lisa Howard was a superb Fosca, Eric Sciotto proved a staunch Giorgio and Shoshana Bean did well as Fosca’s mother).

Berg accomplished this by not concealing Fosca, and not having her suddenly step into the train compartment. Because he’d decided to bring her in from the back wall, the audience could see her long before she’d climbed aboard. Our potential laughter was defused because we’d first seen her look around, find the train, and then enter, thus eliminating our shock and surprise.

Doyle makes a similar move. He too has Fosca enter far upstage and takes his time in getting her on the train. By always keeping her in our view, we know her destination in advance.

Passion gives you a chance to star your best if less-than-glamorous musical theater actress. Conversely, you can choose your most attractive actress and tax your make-up department. Originally, the beautiful Donna Murphy played it wart and all – a big one situated below her left eye. Doyle has spared Judy Kuhn that, but not much else. She looks sickly and sleep-deprived. What’s more, costume designer Ann Hould-Ward has put her in a glorified house dress of dull earth colors.

Clara, meanwhile, goes to town in a golden gown. Melissa Errico is coquettish in giving matter-of-fact advice to Giorgio on how to handle Fosca. Her advice will turn out to be worthless, but she must have the confidence that is the birthright of beautiful women. Cast accordingly.

Giorgio must be amiable, and Ryan Silverman certainly is here. If this Giorgio had lived in the Hairspray era, Corny Collins would probably name him the uncontested nicest kid in town. That works against him in the company of soldiers; one questions his masculinity by noting “He keeps a journal.” (Yeah, you know those writers …)

Seventy full minutes must pass before Giorgio finally snaps at Fosca’s incessant neediness. Make certain to cast an actor like Silverman, one who conveys sensitivity, but is capable of a genuine explosion of justifiable anger.

As for the soldiers, there’s a good deal of choral work for them to accomplish. If you can reassemble your barbershop quartet from your last production of The Music Man, you’ll have a fine head start. Tell your Fosca to go easy on the screams; she’ll need her voice for the rest of the show. She should adopt Kuhn’s brave smile when she says such lines “Hope, in my case, is in short supply” or “I would happily die for you.”

The more cynical among us would say, “Yes, but she has far less to lose by dying.” These are the people who find Passion hard to swallow. Could a handsome and intelligent man really come to love a hideous and infirm woman? That’s for you to decide. But you’ll have to wait to see if your audiences agree or disagree by the amount of applause they give the end of performances. At CSC, the torrential handclaps leave no doubt that John Doyle’s Passion is a success.

Read all of Filichia’s Features!

Read all of Filichia’s Features!

Visit Peter’s Official Website.

Check out Peter’s weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com.

Peter’s newest book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks: A Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award,is available for pre-order NOW!