Tips For Adapting New Musicals From Literature (Part 1)

Tips For Adapting New Musicals From Literature (Part 1)

By EllaRose Chary on November 18, 2011

For the past few months I’ve been writing the MTI Shows In Literature Series. Throughout the posts, I’ve tried to highlight places where the featured musicals navigate common difficulties of adaptation. This post is part 1 in a 2 part series for writers, fans and other musical theater aficionados talking about common challenges of adapting literature for the musical stage. In this series I’ll be discussing these challenges and difficulties more in depth, with tips on how to address them.

For the past few months I’ve been writing the MTI Shows In Literature Series. Throughout the posts, I’ve tried to highlight places where the featured musicals navigate common difficulties of adaptation. This post is part 1 in a 2 part series for writers, fans and other musical theater aficionados talking about common challenges of adapting literature for the musical stage. In this series I’ll be discussing these challenges and difficulties more in depth, with tips on how to address them.Most new musicals adapted from literature have similar problems, all of which stem from a surprising root: love of the source material. Obviously, writers want to adapt material they love because it speaks to them. That love, however, can make it difficult to make the necessary choices required to transform a novel that works into a musical that works. Though it feels paradoxical, sometimes keeping the essence of the story requires losing key parts of the original piece.

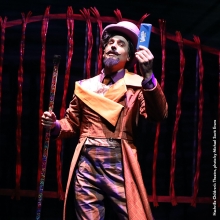

Elements that are completely acceptable in a literary form, such as a number of secondary characters and a variety of locations, can create problems in a script meant for the stage. Characters who speak once and then are never heard from again are missed on stage, in a way they are not in novels. Likewise, jumping between a variety of locations in rapid succession is disorienting on stage in a way it is not in other literary forms. These problems are often compounded in musicals because there may have actually been enough time to introduce the character or explain the location shift in the source material, but in the abridged stage form these people and places appear to come out of nowhere. Often time authors hold on to these elements that drag down the piece out of a love for that character in the novel, or a fondness for that scene in the movie. No one wants to cut their own favorite part of the original – or worse, an audience members' – but that’s the reality of adaptation. Resistance to jettisoning unnecessary elements can be the difference between a successful musical and one that drags. Check out ANNE OF GREEN GABLES for a musical that transforms a complex novel into a streamlined show.

Authors who love their source material often also have a great reverence for the both the piece and the artist they’re adapting. This can stand in the way of a musical theater writer making the piece his own. The mentality that every word Austen or Shakespeare or Dickens or Rowling ever wrote is sacred will paralyze an adaptor. Musicals are so well suited to coming from adapted material because of the way music functions in storytelling. In order to make room for the new depth that comes from adding an adaptor’s voice, particularly as musical numbers, elements from the original must be let go. If it feels sacrilegious to change a particular author’s work, then maybe that’s a clue that the material isn’t well suited to adaptation.

One of the most important rules of musical theater writing is that content dictates form (it’s one of Stephen Sondheim’s three big rules in his book Finishing The Hat). This is as true for subject matter as it is for rhyme structure in lyrics. Poems, novels, children’s books – these are all very different forms than musicals, and in order for a story to successfully move from a literary to a visual and sonic medium the content has to change – whether that’s storytelling mode, plot structure, or number of characters. This reality shouldn’t be disappointing, though, it should be invigorating! Adaptation means changing what you love into something new. Instead of concentrating on what favorite parts you lose in order to make it a musical, I encourage authors to focus on all the ways you’re enriching the piece with exciting, fresh blood in it’s new medium – after all, isn’t that why you chose to adapt it in the first place?

Stay tuned to MTI Marquee for the second part of this series, which will address ways to let music, plot structure and knowledge of the source material serve the show rather than impede it. You can also check out the MTI Shows in Literature series for more tips and examples of shows navigating these difficulties!

EllaRC is a bookwriter/lyricist with an M.F.A. in Musical Theatre Writing from N.Y.U. She has read scripts for several professional theaters including Playwrights Horizons, Berkeley Rep, and BoarsHead Theater. Add her as a friend on MTI Showspace or check out her musical theatre and social justice blog, StageLeft.