Filichia Features: The Scottsboro Boys Live

Filichia Features: The Scottsboro Boys Live

When your audience comes in, they'll see a black woman sitting on stage with a cake box on her lap.

There's good reason for The Scottsboro Boys having the quietest opening that the Broadway musical has ever known. Bookwriter David Thompson wants us to have enough time to realize that this is Rosa Parks waiting for that famous Montgomery bus.

She'll watch with great interest the events that follow. So will discerning theatergoers when they see this intelligent musical about racist politicians in the famous 1931 case and its multiple trials in Scottsboro, Alabama.

It's a tough show, but that's John Kander and Fred Ebb for you. Through their four decades of collaboration that only ended with Ebb's death, they were adventurous: Cabaret, Kiss of the Spider Woman and The Visit proved that. Even Chicago, their biggest hit, was a musical comedy with a snake-like sting.

This story has train travelers Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, about to be arrested for prostitution, saying that they'd been raped by nine young black passengers.

The men try co-operating. One of the accused, Roy, deferentially says, "Anything we can do for you, mister sheriff?" in a most polite voice - only to be castigated by his friend Andy: "Take off your hat, fool; you're talkin' to a white man."

Thompson offers a distressing but brilliant line when the youngest of the nine - a 14-year-old - hears the sheriff's outrage that a black man dared look a white woman in the eye. "Is that what rape is?" he asks - showing us his innocence and breaking the audience's hearts in the process.

Bates eventually recants, but the Southern bureaucracy isn't willing to accept her revised testimony. What sadness there is in her line "Why did everyone believe me when I was telling a lie but nobody believes me when I'm telling the truth?"

Now that Bates has come clean, what can a bigoted Southern attorney general do but attack the defense attorney for being Jewish? So we not only have black bigotry here but anti-Semitism, too. Take a look at the actual court records of April 13, 1933 where County solicitor Wade Wright asked jurors "whether justice in this case is going to be bought and sold with Jew money from New York."

Most of the story centers on Haywood Patterson, whom the prosecution eventually realizes is innocent. The judge makes clear that if Haywood admits to the crime, he'll be lenient on him.

The court is saying that it made a mistake but can't admit it. Freedom is dangled in front of Patterson's face so that the law can save face. If he says he's guilty, the judge can then come across as this merciful good guy who grandly lets him go.

But Patterson won't lie -- and pays a severe price for it. He's convicted and although the judge pro forma says "Any last words?" he and every other court officer leave as Haywood speaks. It's a meaningless formality.

Or is it? Still on stage is Rosa Parks, who intently listens. At show's end, she takes her stand. Rosa Parks, who infamously refused to give up her seat, was also secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP. So Thompson has a point when he postulates that Ms. Parks' action could well have been motivated by seeing what had happened to The Scottsboro Boys.

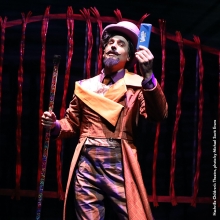

Lest the musical become too bitter a pill to swallow, the collaborators framed it with a minstrel show replete with corny jokes. Your audience will enjoy dispensing their groans.

The show can be done most modestly. Original set designer Beowulf Boritt simply took a bunch of chairs and placed them in intriguing positions - including a tunnel when one of the lads escaped.

Kander's music is outstanding, melodious and memorable. He captured the exhilaration of making your first real train trip in "Commencing in Chattanooga" then conveys the pseudo-elegance of "Alabama Ladies," in which Price and Bates put on the dog to seem refined. What a beautiful song is "Go Back Home," as the Scottsboro Boys imagine being released. When they have reason to believe that they'll soon be given their freedom, they joyfully celebrate in "Shout!" Our hearts break even more because we know they're only at the beginning of their torturous journey.

Ebb gets the story across in concise and precise images. His lyrics in a song about the electric chair harken back to the torture scene in the pair's Kiss of the Spider Woman and "Nothin'" is reminiscent of "Mr. Cellophane."

The The Scottsboro Boys' innate excellence - and its reiteration of the importance of acknowledging our history make this show worthy of attention and good reasons to produce it.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com . His book, The Great Parade: Broadway's Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.