The MTI office will close at 1 PM ET on Friday, May 23rd and remain closed through Monday, May 26th in observance of Memorial Day. Office operations will resume on Tuesday, May 27th.

Filichia Features: Pippin’s Life Has Been Something More Than Long

Filichia Features: Pippin’s Life Has Been Something More Than Long

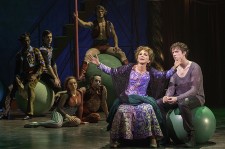

All right, so your theater company doesn’t have a juggler who can keep a half-dozen knives in the air. You’re also lacking a contortionist who can balance himself upside down on a board that rests on unsecured round cylinders. You may not even have a young woman who’s willing to have her body tossed like a sack of sweet potatoes from one man to another. And you probably don’t know a senior-citizen actress who’d be willing to learn how to climb onto a trapeze, let alone feel confident enough to hang from it while a man holds her legs and her head is many perilous feet above the floorboards.

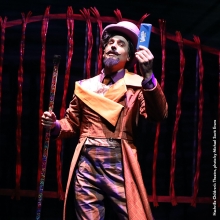

All these ingredients pervade director Diane Paulus’ terrific rendition of Pippin, now an enormous (and deserved) hit at the Music Box on Broadway. While original director-choreographer Bob Fosse had conceived in 1972 that his cast of strolling players belonged to a theatrical company, Paulus instead makes hers into a circus troupe.

As a result, she’s filled the stage with some dazzling Big Top artists. You’ve heard of directors who metaphorically make their actors “jump through hoops?” Some of Paulus’ cast members literally do that.

What’s more, handkerchiefs turn into theatrical canes with just a snap of the wrist. A series of enormous beach balls allows actors to glide over them and go from one side of the stage to the other.

So what Paulus has achieved is monumental. So was what Fosse brought to the stage, which won him Tonys for direction and choreography in a year otherwise dominated by A Little Night Music.

But I’m here to remind everyone that Pippin can work in a far less showy way. Because Roger O. Hirson’s book and Stephen Schwartz’s score are so (to quote a song title) extraordinary, Pippin can easily succeed on Lope de Vega’s famous advice that theater can be done merely with “two boards and a passion.”

Perhaps because Schwartz’s score is so wonderful, Hirson has never received his just due for writing a book that never strays from the message of the show: people may not find happiness in the places they seek it, but may come across it in a totally unexpected area. The trick is to take your happiness where you can find it and not squander the opportunity because you hope that something better will come along. Happiness in the hand is worth many more in the bush.

Three decades before Princeton was looking to find his purpose on Avenue Q, we saw Pippin looking to find his “Corner of the Sky.” The lad would also suffer, as many young men do, from having a super-successful father: Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor. That’s a tough act to follow.

But Pippin will dutifully follow his father into war, believing in his daddy’s goal of “killing every non-Christian.” To Pippin, that sounds lofty, but when he actually murders someone, he’s devastated and realizes that he won’t find happiness on the battle field.

So after Pippin goes to war with men, he goes to bed with women. In Fosse’s production, Pippin casually reached out his arm and happened to touch the breast of a woman who’d been passing by. The lad who’d been searching for The Meaning of Life suddenly looked at the audience, grinned and said, “I found it!” Many theatergoers who had a few more years on them than Pippin gave out with a little laugh. Older-and-wiser folk knew that, no, he hadn’t found what life is really all about.

In Paulus’ production, I did miss one of Fosse’s most brilliant moves. He had one actor hold Pippin’s arms and another hold his legs before they lifted him in the air. A young woman then rolled underneath the spot over which Pippin was suspended and stopped underneath him; the two actors quickly thrust Pippin onto her, then immediately raised him high; the young woman rolled away, just as another rolled in to take her place. The same action occurred over and over again, always with a different young woman. Pippin’s “making love” to these women had all the emotion of a pants-pressing machine doing its daily duty.

What a unique way of showing mindless sex! And notice: all you need to achieve this brilliant move is manpower and not a single theatrical bell or whistle. Oh, wise Lope de Vega!

Once Pippin realizes that he can’t bed his way to happiness, he tries to do some good as a political activist. That means taking on his father and complaining about his policies (the way so many sons do). Hirson is skillful here in the way he shows that if Pippin had the chance to rule, he would, to his unpleasant surprise, do a far worse job than his father. Uneasy is his head when he wears the crown.

What’s left? After a drunken binge, Pippin falls asleep in a field – and is found by Catherine, a widowed single mother. He resists both her and her tween son Theo, but he’ll eventually fall in love with both of them. Pippin realizes that becoming a spouse and a parent may not result in a life that will get his name in newspaper headlines, but that he can get a great deal of happiness by bringing happiness to others. That’s a message that everyone needs to be reminded of or learn.

Lest the show seem too dour or preachy, there’s that ebullient Schwartz score, easily one of the best from the ‘70s, and one that still holds up. The pop-rock music is more than agreeable, which is one reason why “Corner of the Sky” became the go-to audition song for young actors for more than a decade.

As good as the music is, Schwartz’s lyrics excel as well. I’m sorry that current music director Charlie Alterman speeds up the last section of “War Is a Science,” because two of Schwartz’s best lyrics get lost: first, the verbally adept “What separates a charlatan from a Charlemagne” and the truthful “It’s smarter to be lucky than it’s lucky to be smart.” In your production, keep the tempo as it originally was so that audiences can savor these terrific lyrics.

Note, too, how Schwartz gets so much out of a pronoun in “With You,” the song in which he’s pursuing women non-stop. Yes, “you” is a singular pronoun, but it’s a plural pronoun, too. So when Pippin sings that he wants to spend his nights “with you,” he doesn’t necessarily mean one person.

Equally adept wordplay comes at the end of the show. “Think about the sun, Pippin,” he’s told by the entire cast. Yes, the all-American theme of “return to nature” is a big part of Pippin’s theme, but one can also hear the line as “Think about the son” – the son whose life he can greatly enhance.

The score’s crown jewel is “No Time at All,” in which Pippin seeks advice from Berthe, his grandmother. She tells him not to waste a moment, because life speeds by (as any adult will attest). The song has always been a charmer, especially when the audience is asked to join in. Paulus uses projections that display the lyrics which are punctuated with a bouncing ball. You could do that, too, but I prefer Tony-winner Tony Walton’s design for Fosse: an enormous board that represented a piece of sheet music on parchment (in Gregorian chant, yet) was flown in, and a follow-spot demarcated each lyric. Make that one of your two boards.

“No Time at All” was a great show-stopper when Irene Ryan originated it, but Andrea Martin -- that aforementioned senior citizen who does all those gymnastics -- tears the house down to an even greater degree. Fosse, by the way, used Ryan only in that one number, but Paulus wisely makes Martin a member of the circus troupe and keeps her in the ensemble all night long. We like seeing her there.

In the war sequence, Fosse had an actor play a disembodied head. He achieved that by putting him in a trunk with no bottom that was placed over an open trap door; the actor stood beneath the stage and only had his head seen. Paulus does this, too, but does the stunt one better. She puts a beheaded body right in front of the disembodied head, and has had costume designer Dominique Lemieux build a costume of armor that envelops that actor from head to toe. Thus, although this being seems headless, he gestures, gets up and walks off, getting a nice laugh in the process.

While unit sets can be a bore, Pippin profits from Scott Pask’s bridge that has a moveable staircase on each side. A curtain hangs under the bridge, which can hide everything from Charlemagne’s throne to the bed that Pippin will eventually share with Catherine. The multi-purpose design isn’t much more than two boards, but the current cast performs on it with passion.

Pippin is guided through the show by The Leading Player (read: Emcee). He was originally played by Ben Vereen, who won a Best Actor in a Musical Tony for it. Now The Leading Player is Patina Miller, who just might win a Best Actress in a Musical Tony. Moral of the story: pick your best performer, regardless of sex, to play the role. It works regardless – just as Pippin has for decades.

And the show will work forever. Making a spouse and little boy happy is an achievement that will never, thank the Lord, go out of style.

Read all of Filichia’s Features!

Visit Peter’s Official Website.

Check out Peter’s weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com.

Peter’s newest book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks: A Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award,is available for pre-order NOW!

Read more http://mtiblog.mtishows.com/filichia-features-thoroughly-modern-millie-grazie/