Filichia Features: Happy Birthday, Stephen Schwartz

Filichia Features: Happy Birthday, Stephen Schwartz

The invitation for a party being held next Thursday by the Princess Cruises states “Please join us as we announce an industry-first entertainment partnership with the Oscar-winning composer of Wicked, Pippin and Godspell.”

The invitation for a party being held next Thursday by the Princess Cruises states “Please join us as we announce an industry-first entertainment partnership with the Oscar-winning composer of Wicked, Pippin and Godspell.”

They mean, of course, Stephen Schwartz, who’s celebrating his sixty-seventh birthday on March 6.

We can understand why the Princess people touted those three shows. Wicked is already the eleventh-longest running show in Broadway history, and is still doing enough phenomenal, non-TKTS business that it might well double the 4,700-plus performances it’s amassed thus far.

Pippin is worth mentioning, too, for when it closed, it was the eighth-longest-running musical in Broadway history. Not only that, Schwartz’s “Corner of the Sky” became the go-to audition song of young actors everywhere. In 1993, when casting directors were polled and asked what song they never hoped to hear again at an audition, “Corner of the Sky” was the easy winner. And when there’s a song that people are THAT tired of hearing, that’s actually a great compliment, for it means that it’s become a standard.

Henry Hewes, in his Saturday Review review of Pippin, pointed out that anyone who could write a showstopper such as “No Time at All” was worth watching closely. The song is Pippin’s grandmother Berthe’s paean to living life to its fullest, especially because time goes by oh-so-quickly.

Irene Ryan did the number in the original production. She had been famous for playing Granny Clampett, a key character in what was once the nation’s number one TV Show: The Beverly Hillbillies.

At one point Ryan sang, “Now I could waylay / Some aging roué / And persuade him to play in some cranny / But it’s hard to believe I’m being led astray / By a man who calls me Granny.” One might infer that the tail wagged the dog -- that Schwartz added these lines once Ryan had been cast. What’s more, “cranny” and “granny” have two syllables, while in each of the previous sections, the corresponding lines had ended with one-syllable words.

But Schwartz swears, “I wrote that before Irene joined the show. I think, though, that that’s what made (director) Bob Fosse think of getting her. The lyric did go through a change much earlier -- where I rhymed ‘play on some sandbar’ with ‘grandma.’ But I knew it was a really bad rhyme that I had to fix, although I liked the concept of the joke. I thought, let me do ‘cranny’ and ‘granny.’ In fact, I almost changed it when she was cast, because I thought it was tacky. But no one else seemed to be bothered by it, so I let it go.”

And while Godspell “only” ran on Broadway for fourteen months, we must remember it came to Broadway after a five-year off-Broadway run of 2,124 performances. It’s one of the comparatively few scores to have a song taken directly from its original cast album and put on a single 45 rpm record. The artist credited? Godspell, which is as good a name as any for a rock group (and certainly better than such monikers as The Dead Kennedys and Sandy Duncan’s Eye).

So in the nine-plus years between Oct. 1969 and New Year’s Eve, 1978, there were only one hundred and one DAYS when Schwartz wasn’t represented on Broadway.

Some who know their facts and figures might question that 1969 date. After all, Godspell didn’t open until 1971. Yes, but in 1969, the twenty-one-year old Schwartz had a song on Broadway. After his agent Shirley Bernstein had told him that the producers of a new comedy were looking for a title song, he went home and wrote “Butterflies are Free.” All right, he only got $25 a week, but the show ran one hundred and thirty weeks. As Daddy Warbucks likes to say in ANNIE, “And that was a lot of money in those days.” The song made it into the hit 1972 film, too.

But here’s the thing: Schwartz, between Pippin and Godspell’s move to Broadway, had yet another musical open on Broadway: The Magic Show. It ran a whopping 1,920 performances – only twenty-four fewer than PIPPIN – which then was enough to make it the tenth longest-running musical of all time. One of its songs, “West End Avenue,” was one of the most popular cabaret songs of the late ‘70s.

Most writers who’ve had a success of that scope make certain that it’s mentioned in each and every press release about them. But Schwartz has had so many more famous hits – nay, legendary smashes – that he doesn’t even need to mention yet another long-runner.

Not that it’s been all roses. In 1976, The Baker's Wife, despite replacing its inadequate director and recalcitrant leading man during its out-of-town tryout, still couldn’t make it to Broadway. Add to this that David Merrick, the famously difficult producer, had no affection for one of Schwartz’s songs of which the composer-lyricist was quite proud. When Schwartz insisted that it stay in the show, Merrick went into the orchestra pit before one performance and simply removed the sheet music from each music stand.

But ho-ho-ho, who’s had the last laugh for the last four decades? “Meadowlark,” the song in question, became another Schwartz cabaret staple.

It and the rest of The Baker's Wife are a good indication of the immense breadth of Schwartz’s talent. Godspell, Pippin and The Magic Show were filled with a rock sound. The Baker's Wife, however, took place years ago in a small French village, and therefore needed a classic Gallic touch.

It got it. Schwartz’s opening number was a swirling waltz in the best French tradition. Many indeed consider this his best score, while many, of course, do not – simply because there are so many other wonderful Schwartz scores from which to choose. Picking the best is a nearly impossible task.

Only eighteen months after The Baker's Wife called it a life in Washington, Schwartz made it back to Broadway with Working. He’d been smitten by Studs Terkel’s many interviews with workers who told the good, bad and the ugly side of jobs. Because it dealt with people from many walks of life – young, old, black, white, blue-collar, white-collar -- Schwartz wanted a mélange of voices. He enlisted such old pros as Mary (Once Upon a Mattress) Rodgers and newcomers Craig Carnelia and Susan Birkenhead, who have gone on to write Tony-nominated musicals. Add to this African-American composer-lyricist Micki Grant, who’d had a smash hit with Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope and James Taylor.

Yes, that James Taylor, who, when Schwartz had contacted him, had released seven albums in seven years -- from Sweet Baby James in 1970 to JT in 1977 – and saw five of them reach Number Six or higher on the charts. Add to that Taylor’s Grammys for “You’ve Got a Friend” and “Handy Man,” and we’re talking about a major pop artist here.

Many working on Broadway at that time did not have Taylor on their radar. But Schwartz was a product of his Baby Boomer generation, too, and didn’t pooh-pooh contemporary pop while still loving The Great American Songbook. He was as likely to be found listening to Joni Mitchell as readily as Mitchell Parish.

So he invited Taylor, who responded with two memorable songs. Since WORKING, many non-Broadway-centric pop songwriters have come to Broadway, but Schwartz was the first to contact one and get him into the theater.

And yet, Working, despite getting a Tony nomination for each of the above-named songwriters, could only manage three weeks. Add to that that Schwartz was absent from Broadway for the next eight years, and when he returned, his lyrics for the criminally underrated RAGS lasted only a weekend.

Many wags thus decreed that this early achiever was just a flash in the pan, unaware that his best days were ahead of him. Three Oscars would be his for his lyrics to “Colors of the Wind” in Pocahontas as well as its score, and for “When You Believe” for The Prince of Egypt. And while turning his back on Broadway would have been very easy, Schwartz was intrigued by Gregory Maguire’s novel Wicked to adapt it for the stage. It is certain to run longer than his five other Broadway musicals combined.

Schwartz has also helped dozens upon dozens of new and upcoming songwriters in the last couple of decades by being artistic director of The ASCAP Musical Theatre Workshop. Many weeks of the year, he can be found either in New York or Los Angeles listening intently to new songs, giving advice to their writers on how to improve them while also praising what the fledgling writers did right.

What’s more, Schwartz has given something else significant to musical theater: his son Scott. He’s a fine director, as anyone who’s seen Bat Boy, No Way To Treat a Lady and TICK, TICK … BOOM! will attest.

This birthday should be yet another happy one for Schwartz. The stage version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the 1996 film for which he provided the lyrics to Alan Menken’s music, will make its debut at the Paper Mill Playhouse later this month.

And yet, these days Schwartz has to be thinking about a line that he wrote for “No Time at All.” Berthe acknowledges that she’s lived sixty-six years, and that “the only thing I’d trade them for is sixty-seven more.”

Would that Stephen Schwartz could have them. The musical theater would be that much richer for seven more decades.

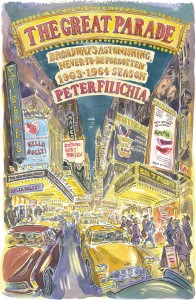

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available for pre-order at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available for pre-order at www.amazon.com.