Filichia Features: Grand Hotel - Fire and Ice

Filichia Features: Grand Hotel - Fire and Ice

The Middle-Age Blues.

We’ve all heard about them, and many of us have experienced them. Donald O’Connor even sang about them (for a VERY short time) in the musical Bring Back Birdie.

If you’re running a theater and have a great number of middle-aged performers who’ve been singin’ the blues over not getting cast or not landing great roles, you can whitewash their complaints by doing Grand Hotel.

Playbill from the Original Broadway Production at the Martin Beck Theatre

There’s plenty for everyone here in this property most famous as the 1932 Oscar-winning Best Picture that had Greta Garbo stating “I want to be alone.”

No middle-aged actor or actress will remotely be alone if you choose to stage Grand Hotel. Let’s use Colonel Doctor Ottenschlag, who functions as the show’s Narrator, to quickly describe the four other meaty middle-aged characters as they walk through Grand Hotel’s revolving door:

“Elizaveta Grushinskaya, the fabled ballerina making her farewell tour. Her eighth.

“Raffaela Ottannio, her devoted companion.

“Hermann Preysing, a businessman reporting to his stockholders.”

(And the reports won’t be good.)

“Otto Kringelein, a bookkeeper looking for life.”

(Because he doesn’t have much left in him.)

Slightly younger is, as the Doctor describes him, “The famous ladies’ man Baron Felix Amadeus Benvenuto von Gaigern, heir to a small title – and large debts.” Substantially younger than he is Frieda Flamm “a typist,” The Doctor tells us. Then, after she flashes her stunning left leg, he adds “But not for long.”

Although Frieda is still in her twenties, she’s just as desperate as the middle-agers. “I want to wear nice shoes” she says in her first song, but she needs much more than that. Her life means “When things get broken, they stay broken” as she tries to keep from breaking down.

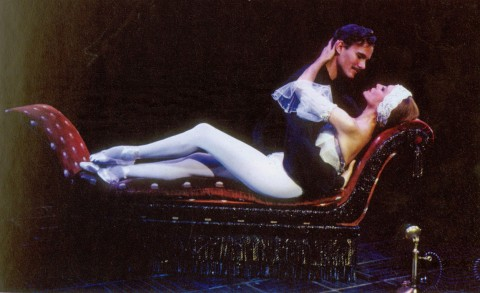

Jane Krakowski in the Original Broadway Production of Grand Hotel at The Martin Beck Theatre (Photo © Martha Swope).

Do you know the term “dramatic irony?” It’s when we know something that the characters don’t. Grand Hotel offers it after Frieda meets the Baron and knows he finds her attractive. She excitedly says “I’m practically a baroness!” Actually, m’dear, you’d better hope you never are, at least not with this Baron, for in addition to his being penniless, he’s also a thief.

We see him break into Grushinskaya’s suite to steal her jewelry – just before she unexpectedly enters. He claims that he’s smitten with her, and she’s ready to believe it. It’s a variation on that famous expression “It’s hard to be poor, but much harder to be poor after you’ve been rich” – for a woman who was a stunner in her youth has a more difficult time seeing her beauty fade than does an adequate-looking woman who was never gorgeous in the first place.

Grushinskaya needs to believe that she’s still attractive, and The Baron is there to tell her she is.

Grand Hotel works best when we too believe that he actually is taken with her and that he isn’t solely a fortune hunter. Don’t misunderstand: he IS a fortune hunter -- but considering who she is (or, more accurately, who she’s been) he IS attracted to her.

You may fear that Grushinskaya’s occupation means you’ll require a crackerjack, on-her-toes elegant ballerina. Relax. We never see Grushinskaya do more than a tour jet é or two – and she is supposed to be well past her prime, so if she doesn’t erase memories of Margot Fonteyn, well, as The Doctor says gleefully, “So Grushinskaya doesn’t sell out anymore.” There’s one of the show’s greatest themes: Time catches up with everyone.

David Carroll and Liliane Montevecchi in the Original Broadway Production of Grand Hotel at The Martin Beck Theatre (Photo © Martha Swope).

The only scene in which we see Grushinskaya “dance” is one where she simply does exercises, pushing and pulling her foot back and forth while keeping it in the air. Showing this scene instead of staging a ballet packs an unexpected wallop; it reminds us that the road to ballet success is a long and torturous one that involves a great many boring exercises. Most musicals show us the glamour of the ballet; Grand Hotel doesn’t, which is in keeping with reminding us that there’s plenty of pain under the surface of life.

That brings us to Raffaela, her assistant who has been saving her money for the day when Grushinskaya will need it – and, most probably, will force her to become her lover.

The show does, however, have a dynamic bolero, and to do it justice you will need two dancers who are astonishingly accomplished.

Of all the roles in the original production, the one that received the most attention was Otto Kringelein, a dying bookkeeper who plans to go out in style by living luxuriously at this grand hotel. Michael Jeter won the Best Supporting Musical Actor Tony – the only performance prize that Grand Hotel received.

Be careful not to have Kringelein come across as too healthy. One actor who succeeded Jeter walked so briskly across the stage that he seemed to be not a dying man but a hypochondriac. So instead of putting a spring in Kringelein’s step, insert some winter into it.

However, when Kringelein unexpectedly comes into a fortune, he temporarily forgets he’s deathly ill and joins The Baron in “We’ll Take a Glass Together.” Take a look at the clip on YouTube and see the greatest showstopper of the last quarter century.

The cast of Grand Hotel at New York University Steinhardt School (Photo © Facebook)

Another important role is Erik, The Front Desk Manager, whose wife is expecting a baby. He can’t be at the hospital, however, because he must work –“or else I’ll lose my job,” he says mournfully. Which of us can’t feel for him and relate to having a boss who “doesn’t care about your personal life”?

There is a happy ending for Erik, who learns through a phone call that he now has a son. Every parent in the audience will understand his song that promises the kid that “You’re going to have everything! Everything!”

That’s more than Preysing expects. His last-ditch hope is that his company will be saved by a merger with a Massachusetts conglomeratern. He’s devastated when he hears “the Boston merger is off.” However, the original production of Grand Hotel found that a Boston merger was indeed on: the joining of forces between original songwriters Robert Wright and George Forrest and show doctor Maury Yeston.

For after the Boston critics gave lukewarm reviews to the tryout at the Colonial Theatre, director-choreographer Tommy Tune asked Wright and Forrest for rewrites. “One couplet a week,” they said, smiling, not taking him seriously.

Tune then made a call to the composer-lyricist he made famous: Maury Yeston, whose Nine had been directed and choreographed by Tune seven years earlier. The result was a Tony-winning musical that also garnered individual trophies for both of them.

As Yeston said to an NYU audience last fall (after he’d seen Dallett Norris’ stunning student production of Grand Hotel), “Tune called me up and said ‘I have a room reserved for you at the Ritz-Carlton’” – which is, ironically enough, Boston’s grand hotel. “I originally thought I’d go and give advice and nothing else.”

And then he saw that the hotel room Tune had booked for him had a piano in it.

Yeston would wind up writing eight songs in the next 21 days. In keeping with the old adage that “Work takes as long as the time you’re given to do it,” Yeston says that he believes “I would have done a worse job if I had had more than three weeks.”

His greatest challenge, he said, was writing a final song for The Baron only three days before the show was slated to move to New York.

“Tune said to me ‘I know you’re tired, but we do need another number for The Baron after his encounter with Preysing.’” Yeston’s response: “But at that point, he’s dead.” Tune’s rebuttal: “Not quite – and they do say that when you die, your entire life flashes before your eyes.”

Yeston reported that Tune wasn’t quite finished with his argument. “‘And,” he said, “The Baron’s the real star of the show.’”

Although Grand Hotel is an ensemble piece, Tune did have a point. Never mind that The Baron pretends to be grander than he is and steals from others’ rooms so that he can keep his own; he does treat the low-borns, including Kringelein, with the same dignity he gives the high-and-mighties. In the end, he gives up his life in order to keep Frieda from being raped.

By this time, Yeston had already written a magnificent, soaring and rangy ballad called “Love Can’t Happen,” which The Baron sang to Grushinskaya. “David Carroll’s voice was one reason why I was able to write it,” said Yeston. (The person you cast as The Baron may well be grateful that Yeston gave him this stellar opportunity to showcase his voice.)

Yeston obeyed Tune and the result was “Roses at the Station,” a fine song in which The Baron realizes that Grushinskaya will be waiting for him and expecting flowers, but he won’t be able to be there. Thus you’ll ideally have a blood bag under The Baron’s tuxedo shirt that reveals a dot of fluid that becomes a veritable red sea.

Tuxedos, gowns, furs – yes, such grand costumes are all needed for Grand Hotel. This isn’t a show for children. (It starts with a needle and certainly not one from an ol’ time record player: The Doctor is a drug addict.) Just as it’s right for middle-aged performers, it’s ideal for middle-agers and seniors, too.

Despite its not being a family show, Grand Hotel was the longest-running musical of the 1989-1990 season. It even stayed on Broadway five months more than City of Angels, the musical that snatched the Tony from its grip. If this were a perfect world, I daresay that directors would be quoting a line from Grand Hotel to describe its Broadway afterlife: “Everybody’s doing it.” Start the trend!

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.