Filichia Features: Gettysburg Still Plays Host to The Civil War

Filichia Features: Gettysburg Still Plays Host to The Civil War

How busy Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was last week! The first four cars I saw while walking around had license plates from Indiana, South Dakota, Kentucky and Wisconsin. Of course, the reason for the congestion was the 150th anniversary of the famed three-day battle that spurred President Abraham Lincoln to say a few words (very few, really) the following November.

How busy Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was last week! The first four cars I saw while walking around had license plates from Indiana, South Dakota, Kentucky and Wisconsin. Of course, the reason for the congestion was the 150th anniversary of the famed three-day battle that spurred President Abraham Lincoln to say a few words (very few, really) the following November.

Chad-Alan Carr, the founding executive/artistic director of the Gettysburg Community Theatre, knew that this was an ideal time to revive the musical that in 2006 had re-opened the once-dormant Majestic Theatre down the street.

The show was then called For the Glory, but Carr decided to return to the title that was used for the 1999 Broadway production: The Civil War. What production could be more apt for Gettysburg’s 150th anniversary than the musical with the Tony-nominated score by Frank Wildhorn, Jack Murphy and Gregory Boyd?

Give Carr credit. Four years ago, he, along with Broadway veteran Karl (Ragtime) Held and others, took an old Elks Hall and turned it into a black box theater. It now sits prominently along the town’s main drag. (To be specific, 49 York Street is its Gettysburg address.)

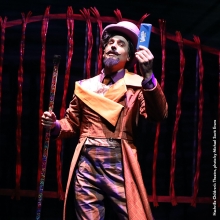

Although Carr himself sang a number dressed as a Confederate soldier, he’s certainly no loser. What he and co-directors Emily Falvey and Greg Trax put on stage made the near-capacity audience applaud and cheer.

True, to fill the house, Carr used the old community theater trick of casting children as supernumeraries so that their parents, grandparents, sisters and their cousins and their aunts would buy tickets. But, really, isn’t this a public service? Kids become accustomed to speaking in front of a crowd; adults who otherwise wouldn’t even notice a theater in town learn to walk through the doors and find something truly wonderful inside. Once they’ve experienced theatrical magic, they’ll be back even when their kids aren’t performing.

And yet, not every young person was an extra. Two young teens were cast as soldiers, one in each army. At first glance, they seemed much too young to be in anyone’s outfit, but history proves that both the Union and the Confederacy took any able-bodied boy. Actually, having inordinately young performers as recruits resulted in added poignancy; while the Union soldiers exhibited unbridled exuberance in “By the Sword” – which was then matched by the Confederates’ “Sons of Dixie” – just the presence of young lads made us sad as we anticipated their fates.

Anthems of war notwithstanding, the show soon returned us to the terrible reality of a slave auction. The directors made us see just from the way that Hector Isidro and Brittani Blank looked at each other that they were a couple deep in love; now they hoped upon hope that they’d be purchased as a unit. One by one, as the other slaves were sold, Isidro and Blank dared to dream that they’d be spared and returned to their current masters. It wasn’t to be, and their heartbreak was well-expressed in “If Prayin’ Were Horses” before they walked off in different directions.

Carrie Trax scored with “Missing You (My Bill).” Here a wife was seen writing a letter to her husband who was off fighting. Much of the letter expressed simple romantic longing, but the wife also related the problems of keeping hearth and home together. She sang that “it’s the work that gets me through” reminding us that plenty of women had unexpected responsibilities long before the many Rosie-the-Riveters took actual jobs in World War II.

But here was the strongest part of the song: neither the lyric nor the singer revealed if the woman were the wife of a Union soldier or Confederate rebel. Of course, that didn’t matter, for we’d feel bad for the couple no matter which side they were on. That’s smart writing.

“Freedom’s Child” had Emanuel Brown play Frederick Douglass, a prominent leader of the abolitionist movement. The directors brought on the young children to sing along and clap in unison to complement Brown’s marvelous singing. Fine, but there’s a good chance that while the kids were learning the song, they asked their directors and parents what it all meant. Once again, appearing in a show can offer plentiful educational opportunities.

Drew Becker sang “Tell My Father,” in which a Union solider who was shot and now dying begged that his dad be informed of how brave he was. The song also served to illustrate another callow reason why men feel the need to fight: to prove that they’re “real men” (whatever that means). How sad to see a life that could have been long and fruitful stopped in its prime because someone had something to prove.

Becker and his directors knew an important theatrical adage: if an actor cries, the audience won’t; if he stays dry-eyed, the theatergoers’ tears will flow. By song’s end, Becker looked positively beatific, as if he had put the war behind him and was now looking forward to his life in heaven.

Another rule-of-thumb: a bitter message delivered in song may be more potent if a rollicking melody is used. Thus “Old Gray Coat” had Greg Trax tell about his uniform. “The waist is shrunk too tight, and the bottom’s caked and muddy and the buttons are half-gone,” he sang, before concluding “but just like you and me, this old gray coat wears on.”

Trax keenly played the subtext of wishful thinking. By this point in the show, any Confederate soldier knew that his side was not going to win. Still, he had to be jubilant in denial before he could face that reality.

The war spared no one. As you’re reading this, somewhere in this great nation, a couple of friends are arguing about politics. But Greg Trax and Mathew Barninger reminded us in “Brother, My Brother” that during the Civil War, two siblings’ differing ideologies might result in their meeting on the battlefield and dueling to the death.

The directors also knew enough to give the show’s strongest ballad to their best singer. April Howard portrayed a nurse who’d just seen her patient die. “I Never Knew His Name,” she moaned, before admitting that she had to “thank God that I never knew his name” -- for if she had, she would have felt even closer to him and would have been that much more shattered. Howard made us feel even worse when she smiled when recalling the soldier’s “bright young eyes,” now that we knew that they’d be forever darkened.

Even without the casualties, there’d be plenty of sobering scenes in The Civil War. The people who are now African-Americans were hardly called that then. And while the word that made Paula Deen infamous is, thank the Lord, nowhere to be heard, “colored” and “Negro” are used.

Two splendid spirituals shone. Emanuel Brown and Brittani Blank returned to do “River Jordan” and Blank paired with Raquel Rivera to do “Someday.” The actors’ faces showed that their characters truly believed that better times were in store for them. But even the triumph felt in these songs was devastatingly undercut by Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech. When Rivera said, “I can take the lash” with great pride, she did establish how strong Truth was -- but that the slave had to endure such treatment was hard to hear.

Carr gloriously sang “Sarah,” a Confederate’s letter to his wife at home. Here was more good direction, for the demeanor with which Carrie Trax’s Sarah read suggested that it was not a letter that had just arrived, but one that had come some time ago, before another letter came – the one from the government that said that her husband had died.

When Sarah then sang “The Honor of Your Name,” our suspicions were confirmed. She told us that he had died and now she must “take the dream and leave the rest; the kids and I might move out west.”

Here’s where the directors got even more out of the lyric. They brought on stage a little boy who wasn’t even yet born when Rock of Ages opened. To be frank, he seemed to be unaware of what was happening on stage. And this worked beautifully. Kids around the age of four can’t know the ramifications of death. If his mother had told him that his father “went to heaven,” years would have to pass before the lad would truly understand what she meant. The little lad’s innocence and ignorance of what had happened made for an even more potent commentary.

There was incisive direction, too, on “The Last Waltz of Dixie.” Not only were Confederate soldiers mourning their imminent loss of the war, but the Union soldiers were doleful, too. They were about to emerge victorious, yes, but now they were facing the reality that 620,000 Americans had died. Their faces showed that they wished the clock could be turned back to a time when the men in charge could have negotiated. To make the point even stronger, the song was followed by an on-stage battle in which everyone died.

One doesn’t need great production values for The Civil War. The “set” was simply a back wall painted with both nations’ flags. They alone told a story: America had 35 states and wanted to keep them, but the Confederate States of America’s flag showed 13 stars of its own.

While The Civil War is basically a sung-through glorified (and glorious) concert, President Lincoln does occasionally comment on the action. The directors used a tape recording of Jim Getty’s voice, but if you have an actor who could pass for Lincoln, use him.

There are plenty of 150th Civil War anniversaries coming up in the next couple of years – including the Union’s ultimate victory over the Confederates in April, 1865. If The Civil War seems right for your town, may you have the same success that Chad-Alan Carr’s Gettysburg Community Theatre had with it last week.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.