Filichia Features: A Chat with Men of Great Importance

Filichia Features: A Chat with Men of Great Importance

So, after seeing a stunning performance of A Man Of No Importance at New York University, I was suddenly in the company of three men of great importance.

Bookwriter Terrence McNally, composer Stephen Flaherty and John Simpkins, the show’s director, surrounded me on a panel I moderated.

I commenced by a McNally line in THE FULL MONTY: “Let’s start at the very beginning -- a very good place to start.” (Those who stayed for the talkback got the joke that McNally borrowed the line from – well, you know.)

I asked who called whom to say, “I just saw this film called A Man Of No Importance and it has to be our next musical.” McNally immediately raised a hand and said he was the first to notice the 1994 movie. What piqued his interest was Albert Finney as the lead and the title that referenced Oscar Wilde’s 1893 hit “A Woman of No Importance.” And if we needed any reminder of every musical’s lengthy gestation period, McNally gave us one by simply mentioning that he’d found the film in Blockbuster Video.

But Flaherty wasn’t initially responsive. “Alfie Byrne is a closeted, pent-up gay,” he said, “and such men don’t sing. It wasn’t until Terrence had the idea of having Oscar Wilde join Alfie on stage, talk to him and give advice that I became enthusiastic.”

McNally and Flaherty were raised Catholic, but Ahrens is Jewish. “Yes,” said Flaherty. “Lynn had to learn about the Catholic sacrament of confession.”

For Alfie goes into the small booth and tells the priest “It’s been a week since my last confession.” McNally’s line had received a good chuckle from the crowd that wasn’t able to imagine someone’s going that often.

“But that was the culture then in Ireland,” said McNally, who had the priest immediately say to Alfie: “A good sinner can get into a lot of trouble in a week.”

The crowd had laughed over “good,” which one doesn’t usually associate with sinning – even if the priest meant “good” in the sense of “thorough” rather than “admirable.” More laughs still came at confession’s end when the priest baldly called the confessor “Alfie Byrne.” The process is supposed to be anonymous. To paraphrase a line from “Chicago”: “Judas Priest! Ain’t there no privacy left?”

Alfie’s job is collecting tickets on a bus, but what he lives for is presenting plays at the local church (although he’ll get in trouble for mounting an Oscar Wilde). When I asked “Do you have any community theater experience?” McNally said he didn’t, although he did recall performing in “Arsenic and Old Lace” while in high school. “I was the dead body,” he said. “They kept shuttling me in and out of that window seat and kept hitting my head.”

Such an experience could turn a man to playwriting. But McNally originally planned to be a journalist, and traveled 1,600 miles from his native Corpus Christi, TX to attend Columbia University. “I knew from the age of 12 that I’d leave,” he said, partly because the town was hardly gay-friendly. “And at 17,” he said in a voice filled with gratitude, “I did.”

Flaherty noted that he’d had an easier time in the more accepting Pittsburgh; of course he also benefited from being two decades younger than McNally and thus coming of age after the Stonewall Riots.

The two noted that Richard Thomas was originally signed to play Alfie. “Then he got a more lucrative offer, and reminded us that he had six children,” he said.

Both collaborators were more than pleased with his substitute: Roger Rees. “He came over to my apartment for two weeks straight, every day, and I was impressed with his native musicianship,” said Flaherty. “We started from the top and just kept on going.”

As it turned out, their fledgling director worked that way, too. “He was Joe Mantello -- before ‘Wicked,’” Flaherty said with a smile. “Joe would always start rehearsals at the beginning of the show and went on from there as far as he could in the day. It worked very well.”

McNally expressed gratitude that Andre Bishop , artistic director of Lincoln Center, wasn’t the type of producer who threatened to close the show during rehearsals if he didn’t get what he wanted. Instead, he arranged for two readings and then two workshops.

“I do miss going out of town and seeing what actual audiences think,” mourned McNally. After Flaherty reminded him that they were out-of-town with Ragtime for 14 weeks, we were brought to that magnificent musical.

McNally was sought to adapt E.L. Doctorow’s novel – “so I read it in a day -- it’s not long – and loved it.” (I told McNally that he must have been an Evelyn Wood graduate, for Ragtime isn’t a particularly short book.)

So McNally was on board. “But I told the producer that when looking for someone to write the score, don’t just find people who’ve won 85 Tonys or just as many Oscars. Get anyone who wants to write the score to send in songs on spec on a cassette,” he said, once again inadvertently reiterating just how long ago this was by using the word “cassette.”

Eight cassettes eventually arrived in McNally’s mailbox. “As I requested, they didn’t have the names of any of the writers,” he recalled. “They were Tape A through Tape H. I loved Tape F best, and everybody agreed.”

“F” as in Flaherty and Ahrens, as it turned out. McNally’s faith was not misplaced, for in that year’s Tony race, Ragtime won both Best Book for his work and Best Score for theirs.

And yet, the three did have different notions of which character was the main one. “I always saw it as Younger Brother and Steve saw it as Coalhouse,” said McNally, to which Flaherty added “And Lynn saw it as Tateh.”

Said my girlfriend after the discussion, “What are they talking about? Clearly the main character is Mother!” (I’m with Flaherty, by the way.)

When they divulged that they’re now working on a stage version of the animated feature “Anastasia,” (for which Ahrens and Flaherty had provided the film score), the audience full of NYU students cooed; it’s a movie they’ve known and loved since childhood.

Happily, the trio isn’t just putting the movie on stage. McNally said he’s re-imagining the property and Flaherty and Ahrens have now written 15 songs for it.

Flaherty also got an “ooooh” from the audience when he mentioned that the first musical he wrote (at 14) concerned conjoined twins for the crowd undoubtedly knew about the musical on the same subject that opened on Broadway in 1997 and was recently revived there: “Side Show.” Here’s a bigger irony: when Flaherty and Ahrens won the 1997-98 Tony Award for Best Original Musical Score for Ragtime, their competition included “Side Show.”

I also reminded McNally that we were about to mark the 50th anniversary of his first-ever play “And Things That Go Bump in the Night” which, coincidentally enough, was booked into the same theater where his “It’s Only a Play” now resides.

There were six New York newspapers in those days, and all six critics panned the play.

“But,“ said McNally, “the next morning (producer) Ted Mann said he had $35,000 left and he wanted to experiment.”

And so, Wednesday’s papers proclaimed “All seats, one dollar.” (That actually represented an 85% discount, because in those days, tickets to plays cost $6.90.) According to Otis Guernsey in his “Best Plays of 1964-65,” about 700 people showed up that night, but the rest of the week was a 1,078 seat sellout.

The following week, tickets were upped to $2 on Friday and Saturday evenings – and still all eight shows went clean. Now the $35,000 was spent, and the show closed. But in the process, Ted Mann once again proved that if seats are cheap enough, people will come.

McNally said that he attended each performance, and, with houses fuller than they’d been in previews, he started noticing where the playgoers were interested and where they were bored. Each performance, he noted, seemed to hold the same peaks and valleys.

“And that,” he said, “was the best education a playwright could have ever had.”

Yes. A playwright can’t learn much from audiences if no one comes. But with full houses, McNally got a crash course in playwriting. “I’d seen where I’d outsmarted myself, where I’d been pretentious, winced at the same points each night and vowed I’d do better in the future.”

Luckily, McNally had an adventurous producer. If he hadn’t, he might well have become in theatrical terms a man of no importance. And then where would Ragtime and A Man of No Importance be?

VIDEO: Ahrens and Flaherty on A Man Of No Importance...

VIDEO: Ahrens and Flaherty on Ragtime...

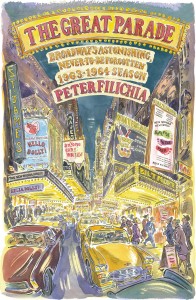

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available for pre-order at www.amazon.com.